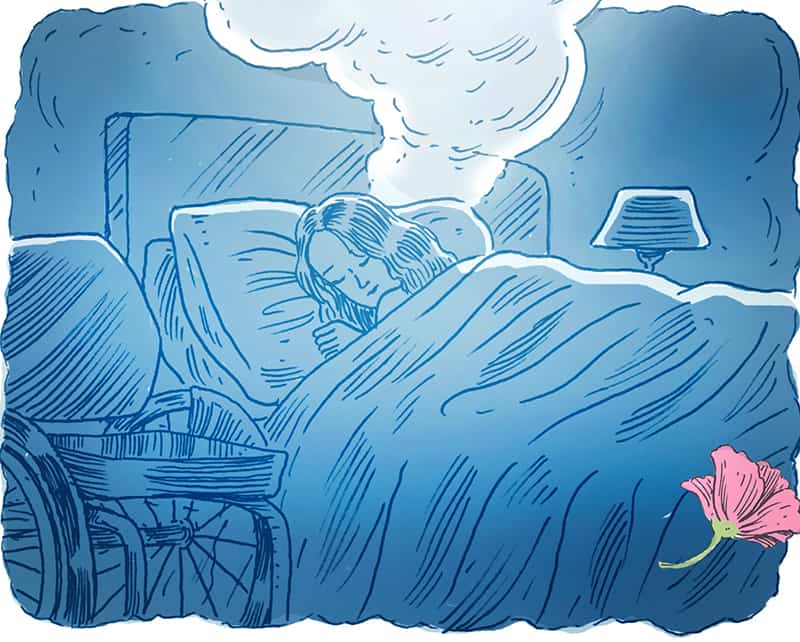

When it comes to my dreams, I’m generally unfazed by spotting polar bears in my bathtub or falling in love with a guy I haven’t seen since fifth grade. What strikes me as odd is that I’m always walking through dreams without my wheelchair, yet I still can’t maneuver stairs. This unexpected new reality is just one of the many puzzling things that I have noted about my dream world since becoming a high-level quadriplegic.

Dream Me is independent and has a full range of motion. Despite showing no visible signs of paralysis in my dreams, my legs often lack confidence. I move slowly, step gingerly and reach for handrails. In dreams, I’m a seeker; I search, and solve puzzles. Recently though, locating accessibility features has become a bizarre recurring theme in my twilight quests. Dream Me has no issue with seemingly endless hunts to locate an elevator in outer space or wandering through labyrinths looking for barrier-free exits.

I’ve started to wonder: Is my subconscious obsession with accessibility unhealthy? Clearly, the theme is relevant to my life, but with my limitless subconscious at its disposal, why isn’t my brain giving me the night off from ADA duty? Am I the only one with a spinal cord injury walking unsteadily up access ramps in my dreams?

It turns out, I’m not. In fact, 60 percent of the 138 people with SCI who responded to a poll I created responded that they, too, are sometimes in and sometimes out of their chairs when they dream. In contrast, most of the remaining 40 percent of respondents never use wheelchairs in their dreams. A big surprise for me was that only a few said they always use their chairs in their dreams.

Many respondents commented that despite enjoying otherwise full mobility while dreaming, they also run into illogical SCI-related stressors. Apparently, the dream world is full of seemingly-able sleep-walkers: dreamers with functioning limbs who still require help with basic tasks, can’t pee in inaccessible bathrooms, give themselves never-ending bowel programs, and — surprisingly often — must push or drag their wheelchair along as they walk.

A New Natural

Wes Holloway, a C5-6 quad, has a unique relationship with his vivid dreams. A fellow nighttime explorer with awkward mobility, Dream Wes never uses a wheelchair. Still, he frequently needs assistance or can’t pass a physical barrier despite ambulating on his own. “Sometimes, I’m walking up a hill without my wheelchair, but someone will lead me with a hand or come up from behind to push me,” he says. “Other times, I’ll be driving without my chair, but simultaneously being concerned I should have it and that what I’m doing isn’t safe.”

Despite a similar level of injury, Elizabeth Treston has no problems with mobility in her dreams. Her gait is normal and she goes and does as she chooses, nimbly and without hesitation. She has dabbled in dream analysis during her 40 years as a wheelchair user, but at this point, she doesn’t take dreams too seriously. Instead, she says, “In dreams, I’m just me. Except, I get to walk around, run, swim, and have great sex.” She coyly reveals, “When I’m dreaming, Steven Tyler and I are the perfect couple. Which is odd, because I don’t really have a thing for Steven Tyler. But believe me, we are a great match.”

For Andrea Dalzell, a paraplegic, dreams might as well be called walks, because that is what she does in all of hers. Without fail she is actively walking away from someone or something. She says, “Some nights, I’m being chased and other times someone is trying to tell me something. What’s funny, is I often don’t want to hear what they have to say and I’m doing what I can to stay far enough ahead of them that I can’t hear.”

Unlike these three dreamers, Jacob Wacker is one of the handful of respondents to dream as he lives, a C5-6 incomplete quad and power chair user. Despite his dreams often taking place in unique locations and featuring novel encounters, his arm movement is limited and he cannot stand or move his legs. If he is alone and something drops, he simply lets it go. If someone else is present, he asks them for help. “It’s just what feels natural,” he says, adding he was stunned to find out most people with SCI aren’t paralyzed in their dreams. “It blew my mind really.”

Subconscious Anxieties

In the weeks since I started this exploration, my own dreams have noticeably evolved with the influx of dream-related discussion and research. Last week, overtired and in a hotel bed, I woke up shaken from a vivid dream where I was very much paralyzed. Specifically, I found myself lying on the pavement unable to move my limbs as spiders rappelled down from their webs around me.

Beyond being terrified, I was curious — had I just experienced a phenomenon called “sleep paralysis?” Or was this just a run-of-the-mill, yet disturbingly spider-filled dream as my quadriplegic self? Beyond the creepy crawlies, the actual sensation of lying on the ground unable to move didn’t feel new or strange at all.

As it turns out “sleep paralysis” is a reference to feeling conscious and awake but being unable to move for short periods while falling into or out of sleep. The sudden lack of control is not a dream at all, but an irregularity or lag in the sleeper’s ability to transition between stages of sleep and wakefulness. In dream sleep, our muscles essentially turn themselves off. So, for some, remaining or becoming aware while transitioning in or out of the dream stage can result in an unsettling momentary paralysis.

In stark contrast to waking up unable to move, for some paralyzed people it’s the sight of the more-mobile dream self that can be jarring. Dalzell says she occasionally dreams she is watching herself walk from above. “I’m acutely aware that my feet are there and I can feel everything. Those are the dreams I don’t like, because I can wake up very emotional,” she says. “I don’t know if it’s a subconscious yearning to walk, but I momentarily forget about my disability as I wake up. Things can feel so natural and real that I forget I can’t just swing my legs up and out of bed. I go to stand up, and I completely miss my chair. I have ended up on the ground more than once.”

Beyond unpleasant wake-up calls and inescapable arachnids, post-SCI life also involves the inevitable dreams that are not dreamy at all. Before he was injured, Wacker had frequent nightmares about ghosts or monsters. “After my accident, I made peace with that stuff. Now, the anxieties I face in my dreams are things I worry about every day,” he says. “My biggest fears are about hurting myself by not being able to get out of harm’s way or falling out of my chair. [In my dreams] I may be out rolling around town with a beautiful girl and feeling a really vivid connection, but I will start to worry that my foot is dragging without me knowing it. If I see that it is, I will feel the hypersensitive sensation the same as if it was actually happening.”

Dalzell expressed something similar, noting that when she isn’t feeling well the perpetual forward motion she’s used to in dreams can slow or stop. “Instead of walking away from someone, I will be walking down steps or sitting on a mountain watching everybody else,” she says. “Sometimes, I’m playing with my feet, which sounds weird, but I will be playing with my toes or my feet will be covered in water or sand.”

Making Sense of it All

While it doesn’t happen often, every once in a while, post-SCI life does barge in on Treston’s dream self. Like Dalzell, it is generally when she is ill or hospitalized. A recent example makes her laugh. “I have a colostomy bag that I call Seymour. In that dream, I was walking with a friend when Seymour began overflowing uncontrollably and spilling out into the air all around me,” she says. “I started frantically looking around for a restroom, but there wasn’t one. Panicked, I asked, ‘what do I do?’ My friend said, ‘Catch it!’ So I did. Suddenly, I was reaching out to catch the floating crap with my bare hands.”

The next morning, Treston thought the dream was so strange that she told a friend about it. “That just means money is coming,” he responded nonchalantly. Treston found the explanation helpful, admitting, “I’m happy to dream that Seymour is exploding if it means a windfall is coming my way.”

If dreaming about poop means money is coming, I was curious what my arachnid-filled dream was trying to tell me. Intrigued, I consulted Google’s extensive collection of dream expertise and interpretational guides to learn what it means to dream that you are paralyzed.

It turns out paralysis has been a heavily-explored theme since the beginning of time. Back then, dream paralysis meant a large spirit had chosen to sit on you as you slept. Recommended solution? Keep a knife near the bed for protection from lazy giants.

The far less interesting modern interpretation attributes paralysis to one’s inability to act on a problem or solution in real life. This explanation seems to cast a pretty wide net, but it’s not wrong. If nothing else, I’m certainly defenseless against spiders.

Holloway says that he learns a lot about himself through dreams. “Sometimes my dreams are exhausting, but the long and complex dreams I have teach me things,” he says. “Perhaps it’s because I have the time to reflect on them more now, but I find them pretty fascinating.” As a frequent dreamer, his dreams — even during short naps — are drawn out and detailed. He can recall multiple dreams from the night before [see Dream Training, below]. “Occasionally, I confuse what is real and what happened in a dream since my friends and family are often main characters,” he says.

For Holloway, dreams are also catalysts to further personal understanding. “My day-to-day life can be boring, but I’m pretty convinced that sleep is my brain’s time to be active and allow me to have experiences that I may not be able to otherwise,” Holloway says. “I feel like at night I’m getting a chance to code my memories and get things formed in my brain. Other times, I feel the opposite, and dreams seem like my brain suggesting I get out and do more.”

Wacker uses dreams to work out scenarios he is considering in his waking life. “I have many problem-solving dreams and I find solutions and inspiration in dreams all the time,” he says. “I have come up with alternate strategies for video games, ideas for projects, and recently, I am able to work through choreography for my performance routines while I sleep.” He finds this very helpful, but notes, “I have to make sure I get the idea down or work through it right away so I don’t forget what I learned.”

The Long Line in Heaven

Sleep is a time for our bodies to repair and take a break from the physical burdens of each day. Dreams play an essential role in maintaining a healthy sleep cycle and given the added physical and emotional tolls that come with SCI, it seems reasonable to assume our dreams carry extra importance.

After SCI, our dreams present a unique environment to realistically explore physical experiences, and for some, feel the sensation of activities we may not otherwise be able to access while awake. Our dreams may not always make sense, but they present an interesting opportunity to reflect and interpret the images we receive to learn more about ourselves. With the introduction of dream training, there is potential to increase our independence and expand our minds as we sleep.

If I’ve learned anything discussing this subject, it’s that we are all unique in the ways that our unconscious brains interpret our daily lives. Oh, and if you can find an accessible bathroom stall in dreamland, there will likely be a line of other sleep-walkers (or dreamers-with-paralysis) standing around waiting for it too.

Dream Training

For many, there are opportunities to manipulate their dreams into tools for both business and pleasure.

Dream incubation is the process of focusing your attention on an issue as you fall asleep in hopes of consciously suggesting the subject of your next dream or posing a scenario to act out as you sleep. The idea being that you can then recall the outcome or solution in the morning.

For the more advanced dream trainer, lucid dreaming takes things a step further by not just simply suggesting a subject of the dream, but consciously taking control of it. Lucidity in dreaming is a coveted skill, and mastering it generally takes training and practice.

For those of us living with mobility constraints, lucid dreaming presents a unique opportunity to fulfill otherwise unlikely fantasies. Like playing a first-person videogame, the dreamworld becomes a safe environment to experiment with alternate realities. All four of my interviewees noted the occasional ability to guide some of what happens in their dreams and exhibit some form of free will. Before his SCI, Wes Holloway worked on lucid dreaming in a psychology class and while he didn’t find himself reflecting much on dreams back then, he finds himself using the skill more frequently now. “I’m able to take charge and do things that I can no longer typically do and I can experience different things that I find pleasurable,” he says.

Experts suggest that would-be lucid dreamers wake slowly to remain within a dream as long as possible. Upon waking, the use of a dream journal or voice recorder can be used to recall and re-examine dream experiences. Then, the focus becomes trying to re-enter a recent dream and look for clues that it is, indeed, a dream. By repeating the last two steps, recognizing dreams and re-entering that dream, there is potential to lucid dream at will and experience the independence and freedom the skill can bring.

Can Dreams Come True?

Given that each one of us is on a unique spectrum when it comes to acceptance of our paralysis, it makes sense that our dreams may reflect our own level of preoccupation with walking and rehabilitation.

For many, dreams are vessels for premonition. Jacob Wacker swears that he had dreams about being paralyzed before he was paralyzed. “Before my accident, I had a dream that stuck with me about being in a hospital bed and not being able to move. It was only after my accident that I realized I had been paralyzed in that dream. It weirded me out, because my hospital room felt unmistakably familiar. The funny thing is, being unable to move hadn’t been particularly strange in the dream. Instead, it felt perfectly normal and made sense to me when I made the connection later reliving my parallel experience.”

My mom too, distinctly remembers pushing me in a wheelchair along on a beach in Hawaii in a dream, something she ended up doing 10 years after my injury.

For Wes Holloway, on occasion, the experiences and conversations he has in his dreams feel like a mechanism for communication with or messages from people he already knows. “If a random friend shows up in a dream, often I will reach out and ask if the scenario means anything to them,” he says. “Three or four years ago, unbeknownst to me a friend of mine had suffered a stroke. During the time he was unconscious and unable to communicate, I had multiple dreams of running into him and felt a strong message to reach out to his family. It’s only when I did, that I found out what had happened.”

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Kelly DeBardelaben on Tips to Maintain Bowel Regularity with SCI When You Travel

Glen Gregos on Traveling With and Without a Caregiver

Sue on Controller Recall Puts SmartDrive Safety in the Spotlight