As a 20-year-old newly-minted para, I learned how to drive with hand controls on the day I was discharged from the hospital in South Central Los Angeles. My older brother picked me up in a humongous 1965 Red Chevy Impala with first-generation hand controls manufactured and installed by a toothless veteran in his Burbank garage. I transferred from the passenger side, slid behind the wheel and pushed on a large lever attached to a telescoping rod that connected to the brake. The accelerator was activated by a smaller squeeze-style lever attached to the larger one. A wire ran from the squeeze lever to a small pulley on the floorboard and looped back to the gas pedal.

When I fired up the engine and squeezed the small lever, my brother and I nearly went airborne screeching out of the hospital parking lot.

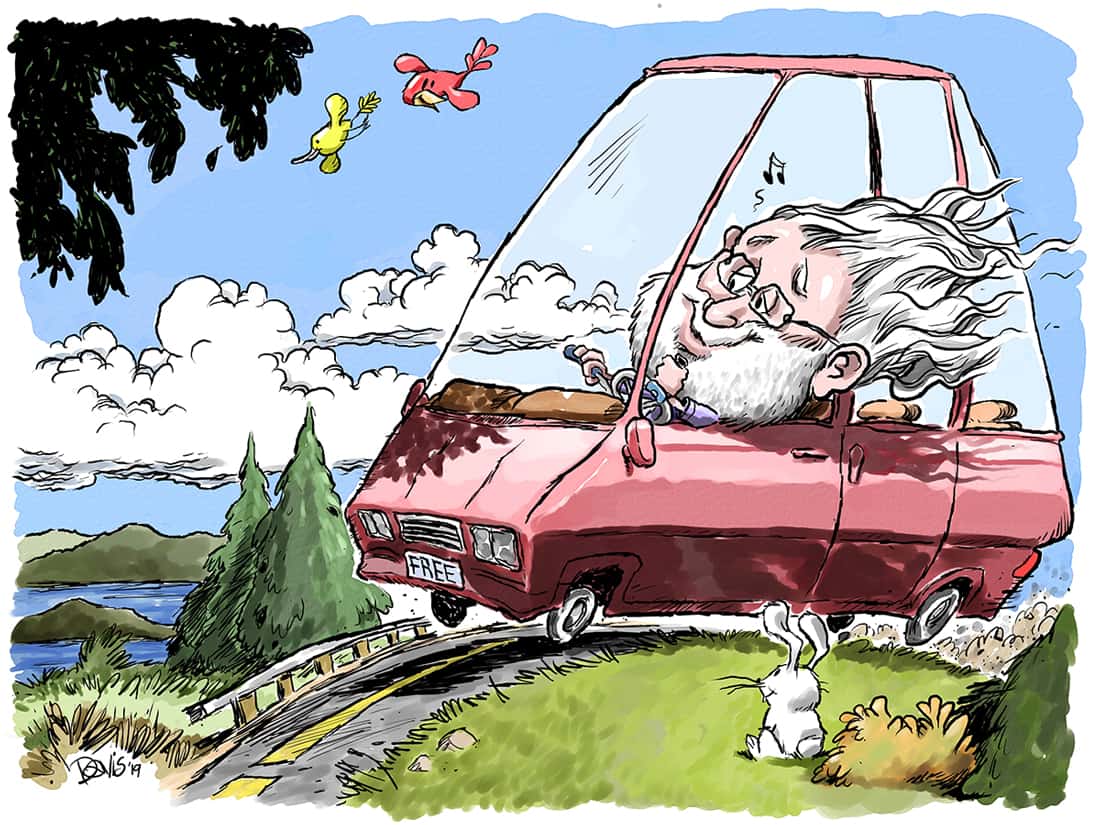

In those early days, windows were useless to me. I was in heaven just cruising the L.A. freeways with my hair flying and the acrid air stinging my eyes. If I needed to freshen up with a clean-air bath, I drove the Pacific Coast Highway, pretending I was the captain of my boat-like Impala. Either way, the reward was in the journey. There is nothing like rediscovering the freedom of movement after losing it.

Last year, 2018, took me back to the hospital days of 1965. Six months of bed confinement led to shoulder problems and loss of strength that robbed me of my ability to transfer into my minivan. Up until then I’d been fortunate in not having to purchase an adaptive vehicle with lowered floors and a lift or ramp. A stock vehicle had always worked for me.

I graduated from those early Chevy rides to stock minivans when they first came out in 1984. Then came my supercrip days as a community college instructor/freeway flyer/farmer. I would transfer several times a day in and out of a Ford F250 Supercab and pull my 50-pound Stainless Sportster folder into the cozy rear seating area and somehow wedge it behind the front passenger seat.

Later, as I aged, I lost the ability to make that Supercab transfer, so I stuck with stock minivans. Years passed. Decades. Heart surgery, then below-the-knee amputation compromised my strength and mobility further. Then came the latest complication, flap surgery. When I finally got the OK to get out of bed in June 2018, after nearly seven months mostly spent in bed and with no driving, I could no longer transfer into my stock minivan.

In Search of the Elusive Solution

After several weeks of being ferried around by my daughter in the cramped quarters of her Ford Focus, I considered my options. Everyone except my wife advised me to get an adaptive van with a ramp or lift. But no way could I afford $50,000-$60,000 for a new one — at 73, I need every penny for living expenses and retirement. Even used adaptive vans cost upwards of $20,000, and they are likely to be very well-used. So I considered a Turny seat, a seemingly simple front seat that rotates outward, slides out of the doorway and drops down for an easy transfer. Simple or not, they cost $10,000 — more than my wife paid for a used 2013 Ford Fiesta with low miles.

There’s a cheaper version that costs about $5,000 — essentially a padded transfer board that flips up at the side of your car seat and moves up and down via an electric motor. But when I visited someone who had one, I saw right away that my car door doesn’t open wide enough to allow me to get into position to even attempt the transfer, plus the transfer board was not all that sturdy. Next idea, please.

How about widening the door opening? I got that done, but it still wasn’t wide enough. OK, how about putting a set of low-rider hydraulics on my van so it will kneel to my geezer transfer level and I can slide right in? No soap. They don’t make them for the front of my van, and even if they did, they’d cost thousands. The question always came back to the same dilemma. How much money was I willing to spend to get something that could either raise me up five or six inches or lower my van down to my sitting level?

Being an inveterate cheapskate, I started thinking low tech. What if I could just make some kind of really sturdy, blocky cushion that I could squish into the space between the front seat and the door, so I could split the big transfer into two small transfers — the first to the new cushion, positioned slightly higher than wheelchair seat level, and the second to the car seat? I raided my hall closet filled with dead wheelchair cushions, got out a pair of industrial-strength scissors and a roll of duct tape, and went to work.

Sorry, necessity may be the mother of invention, but some inventions just aren’t ready to be born. The space in between the seat and the door was too cramped to stuff a halfway decent cushion of any size in there. I ruled out the seat extension approach and went back to my drawing board in hopes of designing a platform with a minimal ramp that would elevate me just enough to make the transfer and still be portable. And not only portable — I wanted to be able to independently load whatever solution I devised into the van by myself while sitting sideways in the seat after transferring.

Eureka!

In a fit of genius, I envisioned a portable platform with minimal tire ramps that would assemble and reassemble in small sections. No section would weigh more than seven or eight pounds. That meant I would have to find a lightweight but strong building material. Carbon fiber would be perfect, but once again, too spendy. Styrofoam might work, but a quick trip to the nearest Home Depot brought me back to my senses. I could rip the stuff into pieces with my bare hands.

What about 3D printing? No, the printed parts would be too large and still might be heavy and unwieldy. On the other hand, wood would work if it was light — maybe — and it was something I could do myself. So I sketched out a simple design for a two-part platform made with one-by-four white pine and covered with 3/8-inch plywood. In my online search for a lightweight ramp, I found a pair of sports car mini-ramps for garage work that were made of hard plastic, but they would only raise my chair up about three inches.

No problem, I could glue two-by-four blocks to the plastic grid-like underside of each ramp and raise them to 4 ½ inches. The platform would still be 5 inches, just a small jump from ramp to platform. But the grid on the underside did not provide sufficient surface for glue to hold the wood. OK then, what about Velcro! Yes, of course, good old Velcro always works. And it did!

I bought the materials and the mini-ramps at a cost of about $150. I sawed and nailed and Velcroed and voila! — I had my lightweight portable platform/ramp, capable of raising me up five inches and being loaded independently, by me, into my minivan.

But the maiden voyage was troublesome. Taking the thing apart and getting it situated in the back of my minivan in a way that allowed plenty of room for me to pull my wheelchair in, casters first — just roll it in and lock the brakes — was strenuous and time-consuming. It took about 30 minutes the first time I did it, and afterward I felt like taking a nap. Now what?

Could it be that the real problem was not my damaged shoulders or my loss of strength or my pocketbook after all? Could it be … oh my God, could it really be … I was a 73-year-old geezer who just couldn’t face the music?

Wife to the Rescue

A week later, sulking at the kitchen table while I stared at my laptop, my wife thrust the classifieds in front of me with a circled ad: “2003 Dodge Caravan with wheelchair lift. 93,000 miles. Runs good but kind of jerky. $6,000 or best offer.”

I called immediately. Why not? Maybe it was time to bite the bullet and get a cheapo adapted van. Maybe I could live with the jerky part. It would make life easier, save my shoulders, my dignity and my independence and not cost an arm and a leg. To my disappointment, the owner did not return my call. So I went back to my low-tech semi-portable platform with mini-ramps. If I could just gain a little strength, maybe I could make the contraption work after all.

The phone rang two weeks later. The owner of the cheapo van had been out of town. Would I like to drive by and take a look at it? “Of course, of course, I’m on my way.”

I transferred into my minivan with the help of my low-tech semi-portable platform/ramp. My wife loaded all four pieces into the back of the minivan for me, and off we went. When I got there and saw the van from a distance, my heart leapt. It looked pretty good, or at least in OK shape for only $6,000. I couldn’t find a good place to park, so I pulled off on the shoulder with my van sloping off on the passenger side and parked in a grassy area — the kind of compromise we all have to settle for when the perfect parking spot just can’t be found. I got out OK, no problem. Getting out is always easier than getting in.

The van, with all the sliding doors open, looked inviting. But the lift worked sporadically, there were bundles of wires running all over the place, the interior was trashed when you inspected more closely, and the bottom of the car was rusted out. My wife turned her nose up at the vehicle and minced no words: “It’s a piece of crap,” she insisted. “I would never own it. A homemade conversion. Nothing but trouble.”

The owner took one look at our faces and immediately lowered the price to $3,000. The drastic reduction only proved the owner knew my wife’s assessment was justified. Sorry, no deal.

To top off my disappointment, when I attempted to transfer back into my minivan using my DIY semi-portable platform/ramp on an uphill grade due to the sloping surface, I didn’t have the strength to pull it off — and fell to the floorboard. My wife helped me, I got in, and we drove home in silence.

Acceptance

The next day I called our local adaptive van dealer and made arrangements to order a Bruno Valet Plus Turny seat that would cost me $9,865 installed. It took a long time to seriously consider robbing my retirement fund to come up with the bucks, but deep down, I knew at my age I wasn’t getting any stronger and my shoulders needed a break. Maybe, after going without an adaptive van all these years, I deserved a spendy automatic seat that would make life easier. Best of all, maybe it would restore my independence.

I had the seat installed right after Thanksgiving. It’s programmable, so the movements and angles necessary to clear the cramped door space worked out just right. By the Christmas holiday I felt like a new man cruising the countryside, rubbernecking, going where I wanted, when I wanted. Sweet, sweet independence!

I know it’s probably an illusion, but I actually feel younger now. It’s amazing how restored independence affects your feelings of well-being and overall outlook. The road ahead looks a lot more inviting these days. I might even go on a road trip to prove to myself that I’ve reversed the aging process. Even if I don’t succeed in turning back the clock, I’ll have a good start on getting my money’s worth.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair