When government entities discuss their plans for responding to natural disasters, people with disabilities have a history of being off the radar. Hurricanes Katrina, Irene and Sandy have shown that the disabled still remain at considerable risk during catastrophic events. While change may not be on the near horizon, it is coming, thanks to efforts by the disability community and a recent decision by the federal judiciary. But until this happens, people with disabilities must continue to watch out for themselves and urge the appropriate agencies to take measureable action.

When government entities discuss their plans for responding to natural disasters, people with disabilities have a history of being off the radar. Hurricanes Katrina, Irene and Sandy have shown that the disabled still remain at considerable risk during catastrophic events. While change may not be on the near horizon, it is coming, thanks to efforts by the disability community and a recent decision by the federal judiciary. But until this happens, people with disabilities must continue to watch out for themselves and urge the appropriate agencies to take measureable action.

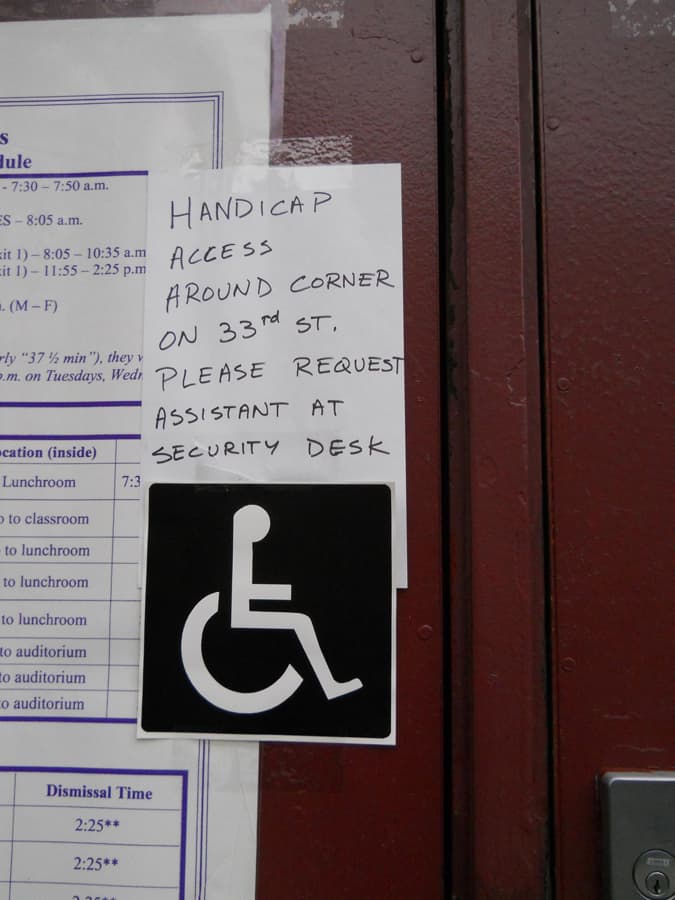

Susan Dooha, executive director of the Center for the Independence of the Disabled, New York, has spent years documenting deficiencies in how New York City assists its citizens with disabilities during disasters. She has seen rickety and steep ramps at shelters, padlocks on accessible shelter entrances, unavailability of transportation when evacuations are ordered, and people trapped in high-rises for days without electricity to power vital medical equipment.

When the same issues reoccurred during Hurricane Sandy, Dooha’s organization, along with the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled decided to sue the city. The November 2012 class action suit alleged the city failed to adequately account for 900,000 New Yorkers with disabilities in its disaster planning, thus putting them in grave danger.

When the same issues reoccurred during Hurricane Sandy, Dooha’s organization, along with the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled decided to sue the city. The November 2012 class action suit alleged the city failed to adequately account for 900,000 New Yorkers with disabilities in its disaster planning, thus putting them in grave danger.

“The city’s response during Sandy demonstrated again that major problems still exist. And this is what happens when the City has days of warning. We can’t wait for people with disabilities to get hurt or die to see change,” Dooha says.

Shelter access during a disaster is vital to saving lives. But for people with disabilities, even going to a shelter is risky because often there’s no guarantee you’ll get in the door or be allowed to have your service animal.

American Red Cross Shelters

The American Red Cross runs 60 percent of the shelters in the United States. They are trying to improve access, but the involvement of the disability community in these efforts is key if tangible change is to be realized.

Mary Casey-Lockyer, Red Cross Disaster Health Services, says every Red Cross-supported shelter is assessed on accessibility through forms that were based on the Americans with Disabilities Act. Efforts to correct deficiencies are made when shelters don’t measure up. “If we find the shelter doesn’t have wheelchair accessibility, then we do everything in our power to make it wheelchair accessible if that shelter is the only shelter in town or closest to the event,” she says.

During Hurricane Sandy, New York City ran their own shelters with help from an ad hoc group of organizations, including the Red Cross. Casey-Lockyer declined comment on the recent lawsuit against the city, but she says Sandy was difficult due to the intricate needs of many people.

The Red Cross has conducted trainings for its employees and volunteers on helping people with disabilities maintain their independence while in a shelter. “We have health services personnel who have RN licenses and can assist individuals with their care,” she says.

People can also have their own caregivers help them with their needs. Casey-Lockyer encourages people to bring things like catheters and colostomy supplies if they are forced to leave their homes. “Those kinds of consumable medical supplies are very difficult to resource in a disaster because lots of times they are done on a mail-order basis,” she says.

Recently, the Red Cross has made efforts to include people with disabilities, service providers and independent living centers in the disaster preparation and planning process. “We really encouraged our chapters to reach out to people with disabilities and the rest of the community, to bring them to the table,” she says. According to Casey-Lockyer, it’s vital for people with disabilities to also reach out to county emergency management officials and their Red Cross chapter. “Those with disabilities know exactly what they need and how we can best help them,” she says.

Disasters are fluid events that are difficult to manage, but Casey-Lockyer understands the frustrations the disability community has. “Disasters impact those with disabilities in a large way, and certainly we can understand that it may appear that everybody hasn’t been taken into consideration,” she says. “I definitely think one can always improve.”

Community Emergency Response Team

When floods inundated Northern and Central Colorado last September, Anita Cameron and her Community Emergency Response Team were dispatched within hours to the Red Cross. “Our task was to communicate via ham radio between the various emergency operation centers and shelters,” she says. The team also assisted with getting food to shelters and sending radio operators with damage assessment teams.

Cameron, a CERT instructor and disability rights activist, felt overall that preparation for the floods was good, but she did see some mishaps during her eight-day deployment. “You still had people with disabilities turned away from shelters, particularly having to do with service animals,” she says. Homeless individuals were also being turned away, but according to Cameron that was quickly resolved.

A family with multiple wheelchair users that needed evacuating contacted Cameron through Facebook during the disaster. One of the disaster commanders became upset when Cameron began assisting the family, but she promptly reminded him that during disasters people with disabilities don’t have it easy. Cameron’s persistence paid off — she was able to connect the family to the proper assistance.

Cameron urges others to understand the hardships that face people with disabilities. “A lot of people with disabilities are prepared as best they can be for something like this,” she says. “When you have to go in a helicopter and if you’re on a vent and they can’t take your chair in the helicopter, hello? … you’re not really going to be able to evacuate.”

The CERT program, operated by FEMA, educates people about disaster preparedness and hazards they may encounter. CERT provides training in areas such as fire safety, light search-and-rescue and disaster medical operations. Using their training, CERT members can assist their neighborhood or workplace following an event when professional responders aren’t immediately available.

Cameron has been involved with CERT since 2005. She says if more people with disabilities became involved with CERT, many issues could be easily improved. “If you’ve got people with disabilities working at the shelters, you won’t have the situation of people with service animals being turned away,” she says.

It’s frustrating for Cameron that she isn’t always seen as an equal within CERT. She rejects the notion that people with disabilities can’t be full team members. “There are all kinds of things a disabled CERT can do,” she says. “If you can’t do search and rescue, you can take notes.” Even though Cameron experiences attitudinal barriers, she says they can be overcome if we don’t give up.

CERT has only a handful of references given to disability in hundreds of pages of training materials. “It’s almost as if people with disabilities are an afterthought,” Cameron says. She wants FEMA to show some leadership and update their manuals so they are more inclusive. “I haven’t seen any appreciable changes since I took the first CERT class.”

The Role of FEMA

According to Cameron, FEMA has been improving, but little change has occurred at the local, county and state level since Katrina. She wants change but doubts it will happen unless FEMA receives more enforcement power.

There is also need for city and county/state emergency management officials to reach out to organizations like independent living centers. “You can start with the big well-known disability organizations, but if you really want to get to the people, you’ve got to go to the independent living centers,” she says.

Cameron is cautiously optimistic about the recent ruling against New York City. She’s concerned because although the disability community may know about the decision, the average person on the street isn’t talking about it. “To me right now, OK it’s a victory, but it’s hollow as long as they’re not doing anything about it,“ she says.

FEMA plays an important role in disaster response by stepping in when local and state governments are overwhelmed. In 2010, the Office of Disability Integration and Coordination was established to handle disability-related disaster issues. Under the direction of Marcie Roth, a well-known disability rights advocate, this division of FEMA is charged with communicating with the public and private sectors and providing them guidance and resources as it relates to disaster preparedness.

Roth’s office has lined up contracts to pre-position supplies and durable medical equipment across the country, if they are needed during a catastrophe. FEMA has also informed the states about Department of Homeland Security grants that can pay for interpreters, accessible transportation and shelter equipment.

During Sandy, FEMA supported local and state relief efforts once they were invited. According to Roth, the agency established a disaster recovery center with accessible communication tools so people with disabilities could quickly apply for FEMA services. They also helped bring in 200 providers to help provide attendant care services to those in the shelters.

The lack of accessible transportation was extremely problematic in New York City during attempts to evacuate residents before Sandy roared ashore. Roth echoed those concerns and said FEMA has been a partner in finding solutions. “We’ve provided a lot of guidance that might be helpful to local and state planners and to the disability community around accessible transportation,“ she says.

FEMA can be a valuable resource, but Roth stresses that people with disabilities bear responsibility for advance planning of their needs. She says if plans aren’t made before the response phase, it’s too late to help people with disabilities benefit much from evacuations, accessible transportation and sheltering.

Roth wouldn‘t discuss New York City’s response to Sandy because the agency can’t compel compliance, but she says FEMA isn’t intended to be involved with initial disaster response. “If what folks are looking for is the federal government to come to their house and take them out of their house, that’s not FEMA’s role,” she says.

Paul Timmons, the CEO of Portlight Strategies, has been in the disaster relief business since 1997. His organization assists people with disabilities around the world who have been impacted by disasters. Timmons has seen many promises and agreements made by government agencies and organizations that supposedly serve those will disabilities but all that matters to him is how the disabled fare in catastrophes.

One of Portlight’s areas of expertise is shelter access. Timmons believes access issues happen because people with disabilities aren’t top-of-mind, but he says don’t expect a shelter to be something it’s not. “You should be able to get in, you should be able to go to the bathroom and you should be able to get a reasonable nights sleep,” he says. “It’s not going to be home.” Complete ADA compliant shelters would be great, but Timmons says making them visitable would be an acceptable goal.

Although FEMA is a major player in Timmons’ world, he says the agency is largely irrelevant to the needs of people with disabilities during disasters “FEMA has done what I consider to be an absolutely wretched job in communicating not just to the disability community but to the broader community what can and cannot be reasonably expected of them,” he says. That’s why he urges people to do their own disaster preparation. “There’s some responsibility incumbent on the members of our community to do what anybody else does and that’s do your homework, do your research and have a plan.

The Red Cross has long had trouble meeting the needs of people with disabilities, but Timmons has been hopeful in the last year because of the dialog the agency is having with the disability community. Portlight is pushing for people with disabilities to be more active at their local chapter. “If you speak Spanish, volunteer to translate. If you cook, volunteer to cook meals for the homeless. If you make a bad-ass cup of coffee, volunteer to make coffee for returning troops,“ he says. “Show your ass up at the local Red Cross and let them see us.“

Portlight has been active and on the ground since Hurricane Sandy. Timmons is thrilled with the disability community’s victory against New York City. “What I hope it does is causes people with disabilities to suffer less in these situations,“ he says. It’s too early to see what the ramifications of the suit will be but Timmons finds the decision to be encouraging. “I think because it’s going to be executed under the authority of a judge there’s a better chance that some of this will result in actual tangible change,” he says.

Time for Solutions

On Nov. 7, 2013, Judge Furman ruled that New York City violated the ADA by failing to provide people with disabilities meaningful access to its emergency preparedness program.

Furman didn’t find that the city intentionally discriminated against people with disabilities, but the ruling is still significant. “At last a federal judge has understood what we’ve been telling New York City that it has not been able to understand for more than 12 years,” Dooha says. “The decision is an incredible validation for our community.”

According to Disability Rights Advocates, which brought the lawsuit on behalf of BCID, CIDNY and two individual plaintiffs, the evidence presented at the trial demonstrated that “New York City: 1. Has no system to evacuate large numbers of people with disabilities trapped in high-rise buildings. 2. It does not know which emergency shelters are wheelchair accessible and affirmatively tells people with disabilities their needs will not be met at shelters. 3. The City also has no protocol to address the needs of most people with disabilities in power outages and lacks reliable and effective communication systems. 4. The City also relies largely on inaccessible public transportation for emergency evacuation and has major deficiencies for this population in its recovery plans.”

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs’ claims.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs’ claims.

Still, the decision likely wouldn’t have happened without active involvement by the local disability community. “It was people with disabilities who experienced the barriers and who took the brunt of the city’s failure to abide by civil rights,” says Dooha. She adds that it was citizens who documented problems when attempts to educate the city failed.

Now the plaintiffs will sit down with the city to craft solutions that will improve the evacuation of high-rise buildings, accessible transportation and shelter access. Implementing these changes won’t be easy. “I think the decision will change things here, but I think it’s going to take a lot of work and time,” she says.

Improperly trained emergency responders and shelter staff is another area where improvement is needed. “We’ve been doing disability literacy training for many years, and I’d hope that one of the outcomes is we could use that expertise to help make a difference in people’s skill levels and attitudes,“ she says.

The saga with the city may not be over, but people like Dooha will continue to advocate for needed change. “It’s so important to realize that we don’t have to just accept the status quo and that when people tell us that nothing can be done or that change isn’t possible — that doesn’t have to be true,” she says.

“We can make the difference.”

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair