On Feb. 16, 1999, Minna Hong, 34, and her husband, Tony, were driving home from North Carolina, where they had recently purchased property for their restaurant business. They had decided to turn the trip into a vacation, maybe even teach their two kids, Megan and Kristopher, to ski. On the return trip to Atlanta, Minna, who hates long-distance driving, offered to take over for Tony, who was tired. “I thought I wanted to be a good wife,” she says. “So I said, ‘You know what, honey, let me drive the rest of the way home.'”

Driving in the fast lane, Minna noticed a tractor-trailor rig slowly inching toward her from the right. She had to do something fast or the truck would crush her Land Rover. “I must have been in his blind spot,” she says. She veered left into the median, and the Land Rover rolled–she passed out somewhere between the second and third roll. “My kids were in the back seat and when I gained consciousness everybody was gone. I was the only one there with a man behind me saying, ‘Ma’am whatever you do, please do not move.”

“Am I the worst, am I the worst?” she asked him.

“Yes, yes, you’re the worst,” he told her.

“Oh thank God,” she thought. Then she heard a policeman say, “One man deceased, two kids on the lawn,” and she lost consciousness again.

Days later she eulogized her husband of nearly 12 years from a hospital gurney. Tony had flown through the Land Rover’s sun roof, dying on impact. Her 9-year-old daughter, Megan, had broken her leg, and her 6-year-old son, Kristopher, had only a scratch. Minna’s spinal cord was injured at T12-L1. The truck driver didn’t even stop.

Weeks later in rehab, when her roommate’s family members came to visit, she looked hopefully up at the door for Tony … and then remembered that he wasn’t coming to see her, ever again. “And you dream, and you think, please come in my dream and comfort me,” she says.

“And that’s how my life as a para started.”

‘Wife and Mother Equals Minna’

“Asian people in general are very … introspective,” says Hong. “So my husband did not write love letters or anything like that. But he gave me a Valentine’s card and he wrote how grateful he was that I was his wife and how much encouragement I gave him, how much strength I gave him,” she says. “Throughout my lifetime that card will be one of my treasures that I pass down.”

At the time of her accident she believed: Wife and mother equals Minna. She was the mom in the suburbs who had her grade-school children wrapped in a big blanket every cool morning. When the school bus pulled up she’d release them like birds and they’d fly into the warm bus. “I just thought my role was to be the best mom I could be and the best wife I could be and that was it.” Her desire to be a homemaker and mom have nothing to do with her Korean heritage, she says–it’s just what she always wanted.

“I didn’t have to work for anything, I just cruised through life,” says Hong. “I never had to struggle for anything. So I think, boy, when this [accident] happened, the shit really hit the fan. I grew up.” Of course, she wishes she could take the accident back, “but I can’t and I’m not going to sit and cry about something that’s not going to happen. I have to move forward.”

The Hongs had just reached the place in marriage where they finally knew they’d make it–they’d be the couple celebrating their 50th anniversary. “We got to a point where we knew that, ‘OK, he’s got my back.’ Period,” says Hong, borrowing a term from such famous television cop duos as Starsky and Hutch. “Twelve years into the marriage, after two kids, and all our dreams were unfolding, finally. So yeah, it was rough.”

She sold the home she loved and bought a new wheelchair-modified house and for a whole year after her accident she clung to her homemaker identity. In front of her children she pretended she was fine. “I’d get up in the morning and make breakfast, send them to school. But I couldn’t wait until they left so I could lie down in my bed and just look up at the ceiling.”

The reality slowly settled in that Tony was not coming home–she had to find her own way through life. “I was lost for a long time,” she says. “It was just an empty hole I had and I didn’t know how to fill it. It was the scariest thing I’ve ever been through. But with paralysis came a serious amount of clarity. When you know that no one has your back and you’re it and your kids’ lives depend on the choices you make, it becomes very scary,” she says. “I knew I couldn’t do it alone so I sought out a shrink, and that really helped.”

Get a Job

Tragedy or not, she still had to get out of bed each morning, and the bills still needed to be paid. “Girl, who’s going to pay for your ride?” she began asking herself. “Who’s going to pay for A, B, C and D? You have to get on your feet.” But she had never worked before–or, more accurately, as the wife of the boss she had never been paid for the work she did–so didn’t think she knew how to hold a “real” job.

She thought long and hard about what type of job she could handle. “I felt comfortable at the hospital,” she says. “I felt, shoot, if something happens to me, what a great place to be!” So she applied at Shepherd Center, her rehab home. “I sent in a resume and I came in and I called every week … ‘Hey, did you get my resume, I just wanted you to know I’m still interested.'” Her strategy worked–she was hired as a part-time research assistant, helping to create long term care plans.

That was three years ago. Now she has learned how to balance home with work. “I’m a mother first and foremost, so working 20 hours a week at first was really good for me because I could go to work when my kids go to school and be home when they get home, so I don’t miss them and they don’t miss me.”

Her working has changed some standards in the Hong household. She used to be an exemplary housekeeper. “Nowadays it’s like, ‘Hey … are your socks clean? Are your underwear clean? If so, have a great day and I love you.'” So what if she can’t sweep or mop like she used to–“I can’t measure myself with the same measure now,” she says. “Plus who gives a shit if I have a slightly dirty floor. When I’m on my death bed I’m not going to say, ‘Was my floor clean?'”

Soon she evolved from research assistant to peer counselor, and now she’s a peer support coordinator at Shepherd. She shares an office with two other people and always keeps photos of her children, fresh flowers and an acorn on her desk. “Acorns turn into oaks with deep roots,” she says.

She’s hardly ever in her office, though. More often than not she’s facilitating a women’s peer support group or meeting new wheelers in the gym, hallway, even parking lots. Hong’s own accident makes it easier for others to speak to her, especially other women with spinal cord injuries. She has sat and talked with an older woman whose husband shot her and then shot himself to death, she has cried with a woman disabled from rape, and she has shared outrage with the woman whose boyfriend picked her up and dropped her on her head, leaving her a quad. “We’re dealing with a very vulnerable population,” she says. “Sometimes they get sick of protocols, so I like for them to see me as a friendly face. I am generally laid back and that helps.”

‘Bless Your Heart’

Often when complete strangers see a wheelchair user down South they feel compelled to say, “Well, bless your heart!” It’s annoying, but not as bad as the nondisabled Asians who take “bless your heart” much further, says Hong, who moved to the United States from Korea when she was a little girl.

Hong’s father immigrated to the states first, then sent for his family. “My father came here with only a $100 bill, looking for a better life,” says Hong. South Korea is densely populated and jobs are sometimes hard to find. Once they immigrated, her parents worked in the garment industry for a while and eventually owned a liquor store. The only English Hong knew at first were her ABCs and the line, “Left a good job in the city,” from the song, “Proud Mary.”

“I immigrated here when I was 9, so I’m caught in the middle between my parents’ generation and our generation. My parents’ friends and family view me differently than younger people or people of different cultures, like Caucasians, see me. I think they [Caucasians] basically see me as doing my shit, while the Asian culture is more like, ‘Oh my God, that poor child.'”

Hong says the Asian attitude is partly rooted in the natural desire of immigrants for their children to do very well. “Since they consider success to be their child is a doctor or lawyer, or married to this person, or drive this kind of car, or this is how much they make, when someone puts disability in the picture it puts the child at the bottom of the totem pole.” She says the resulting shame and stigma means many Asian wheelchair users stay at home. “I apologize for saying that, but it’s what I see,” she says. “It sounds terrible, but it’s the truth.”

Hong says the Asian attitude is partly rooted in the natural desire of immigrants for their children to do very well. “Since they consider success to be their child is a doctor or lawyer, or married to this person, or drive this kind of car, or this is how much they make, when someone puts disability in the picture it puts the child at the bottom of the totem pole.” She says the resulting shame and stigma means many Asian wheelchair users stay at home. “I apologize for saying that, but it’s what I see,” she says. “It sounds terrible, but it’s the truth.”

Also, the individual in many Asian cultures is aware of belonging to a larger unit–the family, the community. “There’s no individualism, you show a good face, you sacrifice for the family, you don’t show what’s inside, you try hard to be the same as everyone else,” says Hong. “But I think this is why we [Asian wheelchair users] need to be seen, because when we are, it’s less frightening for the Asian community as a whole.”

She avoids the Asian market now because of how embarrassed other Asians make her feel, especially when she goes shopping with her children. “I see the pity-look in their eyes. They’ll say, ‘Oh my goodness, what happened to you?’ and they’re pointblank about it.” Worse, they cluck their tongues at her, “Tsk, tsk, tsk, and they get really sad: Oh, you poor thing.”

She has seen other Koreans come into Shepherd rehab, some that are high quads, and wonders how they’re doing. “I’m very vocal. Here I am doing my stuff, but I wonder what they do,” she says. “Especially if they have a language barrier. I wonder what happens to those people who just stay in their house.”

Hong gets emotional as she talks about how it feels to be a Korean wheelchair user. “I seem like I’m dissing the Asian community, but I’m not. I want to be accepted as part of it,” she says. “I, too, am a face of Korea, so how dare they deny me.”

Minna Reborn

On her bad days Hong makes jewelry. “If I have a spare moment my mind starts to wander warp speed, so I started beading and that’s taken on a life of its own, in boutiques in Atlanta. When I’m focused on that, I don’t think about other stuff.”

Other days she’s philosophical. “On my good days I say God’s been good to me in the sense that he’s given me two lives so I can experience life more fully–one as a walking person and one in a chair,” she says. “And both can be beautiful and both are worthy of living, and both to be honored. Life is a gift and I’ve been given two, and so have my children.”

More on her children: “The truth of the matter is I think they’re more adjusted than most people. I hate that my daughter had to grow up faster than she might have wanted to, but she’s awesome. She’s spunky, she just made secretary of her school and she’ll be getting her black belt in October. My son, he’s a kid. He’s dirty, he’s funny, he’s cute and he’s loving.”

Her son says things to her like, “I wish Daddy was here so you didn’t have to work so hard.” Many kids give their moms cards that read, “To the best Mommy in the world.” Kristopher’s card to Minna read, “My mother is the best mom in the world because she does twice as much as other people.”

“I want them to know that people can do anything if they put their minds to it, and I want them to be proud of me. And respect me with all my faults,” says Hong. “I think because of my disability they’ve gained a lot of insight. They’ll be more receptive to people with differences, much more compassionate. And so will their friends.”

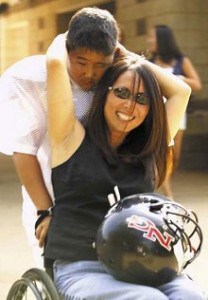

Although she has started dating, Hong won’t fall into the Minna equals wife pit again. “I don’t want to say a man completes me. I want to complete me,” she says. “That’s a huge difference right there. That hole that needs to be filled, it’s got to be filled with me, so I won’t be shaken.”

Ask Hong who has her back now and she says, “Me. And it’s not as scary as I live it, but it is scary.” Her fear of making wrong choices causes her to check and recheck herself, but she says she can handle whatever life throws at her: “I’ve come this far and I think I’ve been through the hardship, so bring it on, baby. Bring it on!”

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair