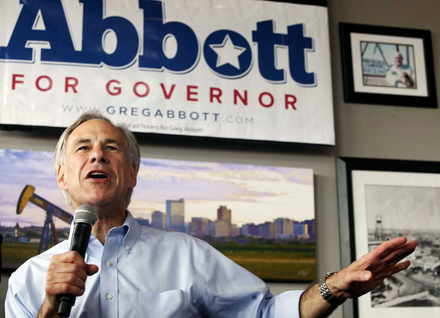

Greg Abbott, 56, current attorney general of Texas and former associate justice of the Texas Supreme Court, is running for governor of Texas. He is a Republican with a robust record as a conservative activist and has by far the largest war chest of any declared candidate — $25 million according to the Dallas Morning News. By some estimates, he is a shoo-in, a worthy right-thinking successor to the current right-thinking governor, Rick Perry.

So, where’s the news there? Conservative Republican voted in as governor of Texas, a state that has not elected a Democrat for state-wide office since 1994? Aggressive, well spoken, an unflinching advocate of gun ownership and tax cuts; an unwavering opponent of abortion, gay rights, immigration reform, and the federal government? Sounds like a dog-bites-man story.

The news, certainly for the Texas disability community and perhaps beyond, is this: Abbott happens to be a T12-L1 paraplegic, and if elected, would be the first wheelchair user elected to the Texas governorship and the first elected to any state governorship since George Wallace won his final term in Alabama in 1984. George Wallace did very little for people with disabilities (he was barely able to deal with the pain and agony of his own paralysis and his much-rumored physical weakness). Abbott, at least conjecturally, could — like FDR, Christopher Reeve, and an elite group of very public figures with disabilities — change the whole perception of people with disabilities in America, and maybe even help herald in an era in which leaders of all kinds will be judged, to bowdlerize Martin Luther King Jr., not by their perceived physical or mental inadequacies, but by the content of their character.

Or not.

Before we explore whether Abbott will be the change-agent who will unlock opportunities yet unavailable to the disabled, let’s first key in on his personal “narrative,” as they say in modern politics. Born in Wichita Falls, Texas, Abbott earned a bachelor’s from the University of Texas and a law degree from Vanderbilt. At 26, he was headed to the top. Then, jogging one day in the very ritzy section of Houston called River Oaks, a giant, 75-foot oak tree, apparently weakened by a storm, came crashing down on him. His spine was crushed, leaving him, after numerous operations, a T12 para.

“What was it like to have a tree fall on you?” I wanted to ask Abbott, along with a laundry list of other questions, but despite multiple attempts from three different people to arrange a phone interview through his campaign press secretary, Avdiel Huerta, we never got a call back. It may be possible that Abbott never even heard about the requests, but it’s pretty clear that his representative, Huerta, saw no upside to talking to NEW MOBILITY.

Rising to the Top

A close and reliable source to Abbott’s recovery and precipitous rise in Texas politics is Lex Frieden, a man with impeccable credentials in the national disability community. Now a professor of Biomedical Informatics (translated: the marriage of high tech and health care delivery) and Rehabilitation at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, Frieden was a central figure in the passage of the ADA in 1990. He has been the chairman of the National Council on Disability, sworn in by the second President Bush, chairman of the board of United Spinal Association, namesake of the annual Texas Lex Frieden Employment Awards, and an advocate on many fronts in the fight for disability rights. After himself becoming paralyzed in a car accident as a college student, he rehabbed at and is now associated with the same facility — TIRR Memorial Herman Hospital in Houston — where Abbott also rehabbed. Frieden, it’s safe to say, has a high regard for the content of Abbott’s character.

“His therapy paradigm,” Frieden says about Abbott, “was to never stop working. TIRR is an exceptional facility. It conditions people to deal with a disability as a kind of problem and approach it with normal problem-solving abilities. Abbott was essentially able to put the whole issue of his disability in the back of his mind … he stayed busy in the hospital. We had to install a second phone line in his room.”

“His therapy paradigm,” Frieden says about Abbott, “was to never stop working. TIRR is an exceptional facility. It conditions people to deal with a disability as a kind of problem and approach it with normal problem-solving abilities. Abbott was essentially able to put the whole issue of his disability in the back of his mind … he stayed busy in the hospital. We had to install a second phone line in his room.”

Abbott had a good idea of where he was headed before paralysis and redoubled his efforts to continue afterwards. He went into law and was a state trial judge, but soon manifested a keen interest in politics — unusual, says Frieden, for a vast number of people with disabilities. “We are,” Frieden says, “an invisible minority as far as the political process is concerned.” In fact, Frieden ran into Abbott at a local precinct meeting, the ground floor of participatory politics. He was impressed. “He was already campaigning before he was running for office.”

About his own rehabilitation, Abbott has said, “The good part was there was always someone there around the clock … there wasn’t much opportunity to get depressed.” This experience may have helped form the realization that he brought into the public arena and repeats on the campaign trail: “Some people think it’s easy to write off the lives of the disabled or the different. But every day, God reminds us that all life has value, no matter the form.”

Abbott, The ADA, and States’ Rights

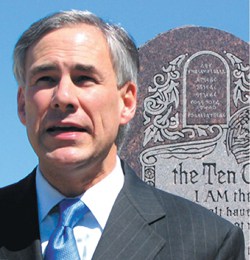

Abbott is no go-along/get-along politician. The cowboy boots he dons are not for kicking cows — they’re for kicking Washington, D.C. As of this last July, he has used his power as attorney general to file 28 lawsuits against federal agencies. He also filed three lawsuits against the George W. Bush administration. Many are still pending, but he has won a bunch of them. He won against the Department of Education for placing undue restrictions on how Texas funds education (the amendment requiring these restrictions was repealed by Congress). He won a number of cases against the EPA and even went all the way to the Supreme Court to defend the right of the state of Texas to have a Ten Commandments Monument on the grounds of the State Capitol.

Many of these victories are common knowledge among informed voters in Texas. “Ten Commandments Monument to Stay” makes for a banner headline, especially in the Bible Belt of Texas. He has also created, statewide, a unit to round up fugitive sex offenders, a cybercrime unit to go after kiddie porn on the Internet, and an effort to go after Medicaid fraud with a vengeance.

Many of these victories are common knowledge among informed voters in Texas. “Ten Commandments Monument to Stay” makes for a banner headline, especially in the Bible Belt of Texas. He has also created, statewide, a unit to round up fugitive sex offenders, a cybercrime unit to go after kiddie porn on the Internet, and an effort to go after Medicaid fraud with a vengeance.

“I think it’s safe to say that he is a states’ rights advocate,” says another tuned-in source, Bob Kafka, a C5-6 quad and Texas-based national organizer for ADAPT, as well as ADAPT of Texas, and along with his longtime comrade in arms, Stephanie Thomas, the 2007 NEW MOBILITY People of the Year. The question is: how does someone with this political philosophy relate to the huge population of Texans with disabilities and their rights and needs? According to the advocacy group, Disability Rights Texas, there are 4.5 million people with disabilities in Texas, arguably the largest such contingent in the country. How the possible governorship of Greg Abbott impacts the lives of these people could impact the lives of all the rest of us.

TheAbbott-generated states’ rights case most people with disabilities will quickly bring up concerns Title II of the ADA. In 2003, a blind Texas Tech professor sued Texas because the school refused to install high contrast tape in the halls to help her get around. AG Abbott would have none of this. He declared that Texas was protected by the constitutional principle of “sovereign immunity.” Under the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a state can’t be sued in federal court unless the state legislature agrees to waive its sovereign immunity. In Abbott’s interpretation, this meant that Texas was exempt from federal Title II provisions focused on physical access and accommodation. He lost the case on a civil rights argument but won the hearts of conservative Texans. “I didn’t invent the phrase ‘Don’t Mess With Texas,’” he proclaimed on a campaign stop, “but I have applied it more than anyone else ever has.”

So, Abbott opposes the ADA? No, he has been quoted as saying he was just doing his job for the great people of Texas. “I love the ADA,” he said in a previous NM article. “Not only do disabled people need it, our aging population makes the ADA vital.”

But, constitutionally, the ADA shouldn’t mess with Texas.

Frieden can see Abbott’s position clearly without necessarily championing it. “In making this sovereignty claim, Abbott acted in his role as an elected state official, and as the state’s pre-eminent defense attorney. From a philosophical perspective, his defensive actions … have evidently been supported by a majority of the Texas electorate.”

But Frieden has one caveat: “Nevertheless, I suspect many Texans, including me, have wondered why he did not simply pass on this particular opportunity to challenge the federal government’s constitutional prerogative.”

Abbott does not back down from his position. Kafka went to an Abbott rally where Abbott promised not to give up this particular ADA fight. Stirring heartfelt historical touchstones of 1840s Texas independence — the Alamo (where they famously lost) and San Jacinto (where they won a month later) — Abbott declared, as Kafka recalls, “that we will ultimately prevail like we did at the Battle of San Jacinto!”

There are many more examples where Abbott has stood up for the rights of Texans, as he sees them, and refused to be bullied and restricted by social mores or financial burdens embedded in laws passed down by Washington. He has publically remembered as a kid “feeling the grip of a gun” (message: don’t mess with Texas firearms). And recently, he announced he would file a federal lawsuit against a newly-passed San Antonio nondiscrimination ordinance relating to sexual orientation, saying it would infringe on religious freedom and violate the state’s one man/one woman marriage law.

Abbott’s attitude about gay marriage recently surfaced, strangely enough, concerning gay divorce. Two men who were married in Massachusetts want to divorce in Texas, but Attorney General Abbott says that would be an unfair imposition of other states’ values on values of Texas. If you allow two gays to be divorced, that means you acknowledge they were married in the first place. As Slate magazine points out, “these cases have placed Texas’ highest state officials in the ironic … position of fighting to keep … gay couples married to one another.”

The ongoing national and statewide debate on voting legality and/or voter suppression laws, depending on your political bent, also has Abbott planting his stake firmly on the side of Texas to make its own voter ID laws and not have to muck around with federal oversight. This could have a major impact on voters with disabilities. As Edie Surtess of Disability Rights Texas points out, the state is rife with inaccessible polling places — new rules and regulations could create more confusion among people who already have trouble voting. There are ways of getting around polling place hassles, says Surtess, like curbside voting, but voters with disabilities are poorly informed about this.

The Abbott Persona

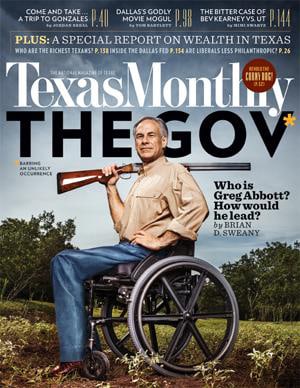

You will see or hear the word “fight” in virtually every extended public statement Abbott makes. If Texas A&M Heisman-winning quarterback Johnny Manziel is Johnny Football, Abbott is Greg Fighter. And he often connects that fighting spirit to his fight to overcome paralysis. This kind of rhetoric drumbeat dispels the common, often unconscious bias that someone with a disability is ipso facto weak, sickly, or mush-minded. But Abbott isn’t just aggressive. He’s “Texas” aggressive, swinging so far away from the soft-hearted, feel-my-pain, I-need-help disability stereotype as to become almost a stereotype in the Arnold Schwarzenegger “hasta la vista, baby” he-man mode. But it’s apparently no act. Regarding his first judicial race, Texas lawyer Pat Mizall is quoted in the Texas Tribune as saying, “It wasn’t enough for him to win … it was important for him to crush the other side.”

[EDITOR: In three state elections — 1998, 2002 and 2006 — Abbott has defeated his Democratic opponents by a margin of a 58.9 percent to 39.5 percent of the combined total vote.]

The gunslinger persona is reinforced at every available turn. Frieden describes an ad Abbott ran while running for attorney general. The message is crystal-clear: “Abbott was depicted rolling his wheelchair across the street flanked by members of the Texas Rangers and the Texas Sheriff’s Association. To see this image on your television of this man in this gleaming wheelchair wearing a suit and leading this army of gun-toting Texas Rangers made you think … ‘it doesn’t matter if you’re in a wheelchair, if you can lead the pack, you can get things done.’”

Abbott has an undeniably inspiring story to tell, and though it is often just a warm-up to his focus on hot-button issues like immigration and abortion, his very presence in a wheelchair — without shame, self-consciousness, or excuse — makes him a potent public presence. He himself has said that just by demanding his own access to hotels and courthouses, “I’ve opened doors for the disabled in ways that no lawyer who brings lawsuits ever will be able to do.”

Abbott has an undeniably inspiring story to tell, and though it is often just a warm-up to his focus on hot-button issues like immigration and abortion, his very presence in a wheelchair — without shame, self-consciousness, or excuse — makes him a potent public presence. He himself has said that just by demanding his own access to hotels and courthouses, “I’ve opened doors for the disabled in ways that no lawyer who brings lawsuits ever will be able to do.”

Frieden agrees: “He has had a profound impact on access in Texas and disability awareness in Texas simply by his very public presence. And he has never, ever made an attempt to hide his wheelchair … if you look at the photographs of his stump speeches, you will see that he uses a specially designed dais that does not cover his legs but in fact is a single pole that emphasizes the fact that he is in a wheelchair.”

Kafka of ADAPT acknowledges that “it’s a good thing that a person with a disability can run for governor in Texas” without a lot of blowback. Kafka thinks this new reality is bigger than Greg Abbott. “It’s really a tribute,” he says, “not to Greg Abbott, but to the whole disability community. It’s a big statement on how far we have come.”

A possible crack in Abbott’s air-tight public image is a widely-disseminated controversy about the financial windfall from his accident. An article in the July 13, 2013 issue of New Republic summarizes the issue succinctly:

“The accident [that left him paralyzed] became an issue in Abbott’s 2002 race for attorney general, when he criticized his Democratic rival for being a personal injury lawyer. Don Riddle, the lawyer who represented Abbott in his own personal injury suit against the owner of the tree and the company that took care of it, suggested his old client was being a hypocrite. Abbott’s settlement is reported to exceed $10 million …”

According to the Associated Press, Abbott has collected in excess of $5 million to date but has no obligation to reveal this in tax returns because personal injury settlements are generally not regarded as taxable income — and Texas has no state income tax, anyway. The terms of the settlement, according to the AP, are that Abbott is guaranteed monthly deposits of $14,400 and every three years, a lump-sum payment. In 2010, that payment was $350,000.

According to the Associated Press, Abbott has collected in excess of $5 million to date but has no obligation to reveal this in tax returns because personal injury settlements are generally not regarded as taxable income — and Texas has no state income tax, anyway. The terms of the settlement, according to the AP, are that Abbott is guaranteed monthly deposits of $14,400 and every three years, a lump-sum payment. In 2010, that payment was $350,000.

As Kafka points out, Abbott, a law student at the time of his injury, had no health insurance, and this settlement most likely allowed him to pay his medical costs and get on with his life. The irony, Kafka says, is that, barring other personal resources, “his hospital bills would have most likely gone to Medicaid.”

“In the state of Texas,” Kafka adds, “Medicaid is the kind of program that people love to hate.”

Abbott and the Disability Community

Abbott’s gubernatorial campaign is in its early stages — he still has a Republican primary ahead and no Democratic opponent has yet been picked. Even so, he has been the attorney general since 2002, longer than any other AG in Texas history, plenty of time to make his feelings known about issues most critical to people with disabilities. But, according to Kafka and Stephanie Thomas, he has kept his cards well-hidden. He has little or no public contact with the larger Texas disability community. “In my knowledge,” Kafka says, “he has never directly addressed a disability group … never gone to one of the state coalitions … not interacted much with anyone in the disability community.”

He adds: “I don’t believe he sees himself, in the cultural sense, as being a person with a disability.”

People with disabilities, in Texas like everywhere else, need help. According to a 2013 Texas Department of Aging and Disabilities report, there are 822,000 aging and disabled Texans below the poverty line, 532,000 of them under 65. Kafka points out that there are 100,000 Texans with disabilities on waiting lists for home and community based services, via Medicaid waiver programs, ranging from basic attendant services to architectural barrier modifications. Will the state legislature allocate the funding for this? More germane to this article, will the presumptive Governor Abbott make this a funding priority?

Kafka also notes that Texas has “one of the largest number of people in state-supported living centers.” Will Abbott lead the charge, via a U.S. Department of Justice settlement agreement, to move those qualified out of these facilities [“living centers”] into community-based living arrangements?

All of these are questions without answers because Abbott has not addressed them in any forum and has not been asked to address them by the mainstream Texas media. The issue with the ADA and the principal of sovereign immunity got plenty of coverage when it came up 10 years ago. More recently, Abbott has said that he will do everything in his power to gut the Affordable Care Act, but no one has asked him the disability-related consequences of that, such as, “What would he do with all the people in Texas with pre-existing conditions, a large number of whom are disabled?” The emphasis so far has been all about his personal story of rising from the ashes of paralysis and nothing about aiding a whole community of people with disabilities in doing the same.

Kafka frames the issue in a larger ideological context. “Many people,” he says, “with disabilities, good, bad or indifferent, are on federal programs” or protected by federal statues like the ADA. “So the question is, these programs that we’ve advocated for — the federal/state program of Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, a federal mandate, and many others — how do these federal programs comport with his states’ rights stance? This is the number one elephant in the room from the disability point of view. Does political ideology, in other words, trump the assumed needs of real people, people disabled just like Abbott?

Spine of Steel?

This may be the most powerful image Abbott evokes in his run for office. A spine of steel conveys power, endurance, and an unbendable will. No matter how he feels about the needs of other people with disabilities, he himself is not asking anyone for anything to redress his own disability or to treat him any differently than any other Texan trolling for votes. He certainly has not made a special plea for disabled voters to support him. His base, it appears, are hardcore, government-leery Texas conservatives, not the “diversity base” that elected President Obama, which includes the most vocal leaders of the disability community.

Whatever its impact, politically or culturally, Abbott belies every stereotype disabled people have been trying to eradicate for well over a hundred years. He is not a victim, not deviant or strange, not sweet and ineffectual, not a burden, and not isolated and alone. He is an inspiration, a hero, something many people with disabilities find offensive (a way to brand them “special” and not “normal”). But it is easy to see how a Texas high school student in a wheelchair struggling with his identity could be inspired by such a forceful public figure. In campaigning, Abbott uses his uplifting story, often without saying a thing, but as Frieden points out in a recent New York Times article, he is not “preoccupied by his disability … his wheelchair to him is the same as eyeglasses to a person who wears eyeglasses.”

And no one will ever run on the slogan, “Vote for me! I’m a good person! I wear eyeglasses!”

A “spine of steel” married to a man in a wheelchair is what the Washington chatter class calls good “optics,” a visual image that stays with voters. Good optics is George W. Bush seen going to church on Sunday. Bad optics is John Kerry donning camouflage to go hunting or any image on Anthony Weiner’s Twitter account. The thing is, good optics can be a shrewd political ploy or something that resonates beyond elections. In Abbott’s case, it could be both.

Frieden fervently hopes that Abbott is seriously challenged. “The real telling dynamic to me in this election,” he says, “is whether the other side really takes him on or gives him a pass. If they challenge him, it shows me that they respect him. If they give him a pass, it actually sends the opposite message, in my view. In either case,” he adds, “I expect him to win by a sizable majority, just as he has in every one of his previous elections.”

Greg Abbott — and you can take this any way you like — is a cowboy in a wheelchair. It comes down to which facet of Abbott most reverberates with you if you were to step into a Texas voting booth (assuming you could get in). If you are disabled and your politics line up with his, it’s a slam dunk of a choice. But if you are disabled and are even a political moderate, let alone an advocate for disability rights and services, you have a conundrum on your hands.

Of course, when candidates get into office, and especially if they are eyeing higher office, their priorities can change. Sitting in the Texas governor’s chair, Abbott could conceivably reverse his course and become a disability rights advocate himself. Stranger things have happened in politics.

In any case, any time the captain of any ship, the leader of any band, the guy in any corner office — is in a wheelchair — you might assume it’s good for all people in wheelchairs.

We’ll see.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Dear Editor:

The article on Greg Abbott was a fair description of his politics and his motivation as a person with a disability to become Governor of Texas.

There is one correction on a statement attributed to me, saying I heard Attorney General Abbott make about declaring a victory at the Battle of San Jacinto. The issue he was referring to in his comments was about how Texas would prevail over the Affordable Care Act in the courts not the ADA. He made the analogy that, the Supreme Court ruling that the ACA was constitutional, was like the lose Texas received at the battle at the Alamo but that Texas would ultimately prevail at the Battle of San Jacinto.

ADAPT of Texas has just started a new non partisan Disability Voting Action Project (DVAP)to better involve Texans with disabilities and our supporters in what will be a very exciting political season in Texas.

Don’t Mourn…Organize, Register and Vote!

Bob Kafka

ADAPT of Texas/DVAP

1640A East 2nd St

Austin, Texas 78702

adaptoftexas.org

Very disingenuous for Mr. Abbott to call himself a door opener for people with disabilities while using his office to deny ADA protections to fellow citizens. I hear his argument that he is the state’s defense attorney. Of course, as governor he would be elected to serve all Texans, nobody’s attorney. A very direct way for Mr. Abbott to counter his inconsistencies is to state that, if elected, he would prioritize the waiver of sovereign immunity to ADA violations. That would align with the overwhelming majority of Texans who hate discrimination for any reason.