Viewing a sleek red Quadra wheelchair demo my first day in the physical therapy gym was a milestone in helping me accept my T10 paralysis. The year was 1985 and at age 25, self-image was extremely important, especially since the folding wheelchairs of the time sent the message: “Patient — don’t touch.” Instead, the red Quadra broadcasted “performance,” “athlete,” “sexy,” “cool!” The PT gym became a mandatory stop when friends would visit me in rehab. “Check it out. This is the kind of chair I’ll be sitting in,” I’d say, a way of letting my friends know I’d be fine.

Quadra is the brainchild of Jeff Minnebraker, who was a recreation therapist at Rancho Los Amigos rehab in Downey, Calif. Minnebraker, an L1 paraplegic, was a licensed airplane pilot with a passion for engineering and a talent for thinking outside the box.

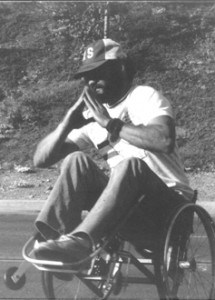

A competitive athlete, Minnebraker incorporated his aviation and engineering skills to build the first ever aluminum, rigid frame, high performance, lightweight adjustable chair. Weighing around 22 pounds, the chair gave him an advantage in sports, and a coolness factor that was coveted by other wheelers. In his continual quest to improve the form, performance and precision of the chair, Minnebraker earned at least 10 patents.

Through his rec therapy, coaching, and athletics, Minnebraker became a mentor for many wheelers. He was competitive in a variety of sports, including wheelchair racing and basketball, and he helped introduce new wheelchair sports, including wheelchair football, which evolved into the Blister Bowl. He also invented the “two bounce rule” for wheelchair tennis — wheelers get two bounces instead of one — that enabled the evolution of the sport.

Birth of Quadra

In 1976, a filmmaker heard about Minnebraker, who was 26 at the time, and made an award-winning documentary about his life entitled Get it Together (vimeo.com/19422433). Among the people at a screening of the film were Jon Voight and Jane Fonda, cast as leads for a soon-to-be-made movie called Coming Home. Voight was so taken with Minnebraker that he studied with him at Rancho and hired him as a consultant for the movie. People who know Minnebraker say Voight became Minnebraker for the part. Minnebraker also appears in the film as a background actor.

One of the people in Get it Together was Brad Parks, an 18-year-old T12 paraplegic who had been injured eight months earlier and had rehabbed at Rancho. “Jeff was helping me learn to play wheelchair tennis and there was an instant bond,” recalls Parks. “During the day of shooting we became buddies.”

At the time, Parks was attending University of California, Santa Barbara, and would stop by Minnebraker’s house in Woodland Hills on his way home from school. One day Parks asked if he could sit in Minnebraker’s chair. He transferred out of his Stainless Super Sport 48-pound folding chair and into Minnebraker’s chair. “The chair felt incredibly light and quick compared to my slow bulky chair,” says Parks. “Jeff had transferred into my chair, and when I looked over at him I was shocked! He looked so handicapped. I said, ‘is that the way I look?’”

At the time, Parks was attending University of California, Santa Barbara, and would stop by Minnebraker’s house in Woodland Hills on his way home from school. One day Parks asked if he could sit in Minnebraker’s chair. He transferred out of his Stainless Super Sport 48-pound folding chair and into Minnebraker’s chair. “The chair felt incredibly light and quick compared to my slow bulky chair,” says Parks. “Jeff had transferred into my chair, and when I looked over at him I was shocked! He looked so handicapped. I said, ‘is that the way I look?’”

Parks asked Minnebraker if he would make a chair for him. The reply was “Nope, but I’ll teach you how to make your own.”

Minnebraker had a shop in his garage and led Parks through the steps to make his own chair. “The first time I sat in it, it was so cool! It moved effortlessly, as if it was part of me,” Parks recalls.

Parks, enthralled by the chair, asked Minnebraker about starting a business. Minnebraker had envisioned this for years and had already drawn up a business plan complete with a copyrighted name, Quadra Transports — later shortened to Quadra. Parks would get a 10 percent share of the company, with the rest going to Minnebraker. They started building chairs in Minnebraker’s garage.

During the same period, Minnebraker was working with a 17-year-old named Eric Walls, a surfer who became a T6 para after falling out of a tree he had climbed in order to get a look at the waves. When Walls got out of rehab, he had Minnebraker show him how to make a chair as well. Soon he also joined Quadra, complete with a 10 percent share of the company. The three were all in. Minnebraker resigned his lucrative job with full benefits at Rancho, and Parks left school — one year shy of his bachelor’s degree.

They spent their days building chairs in Minnebraker’s tiny garage for a quickly growing list of customers.

In 1977 Minnebraker met Mary Boegel (then Mary Wilson). Boegel, a 26-year-old L1-2 incomplete para, was a rec therapist, athlete and tomboy with jaw-dropping good looks. Prior to her injury she was a lingerie model, and had a brief stint as a Playboy Bunny … until she threw a drink in a customer’s face when he got fresh.

Boegel worked as a rec therapist at Ralph K Davies hospital in San Francisco, where she enjoyed good money, full benefits and a nightly commute over the Golden Gate Bridge to her condo overlooking San Francisco Bay in the picturesque town of Sausalito.

Boegel and Minnebraker became close. At a wheelchair track meet in New York, Minnebraker surprised Boegel with the ultimate courting gift — in lieu of flowers and chocolates, he gave her a Quadra. “When I got in it I felt like I was floating, like I could just fly with a slight breeze,” says Boegel. “Then it really hit me. I felt like my disability went away.” It was a realization of how much equipment defines ability. “I was already taken with Jeff. The chair put it over the top!”

With a passion for the chair and for Minnebraker, and with the vision to see the life-changing possibilities the chair offered, Boegel resigned her job, sold everything, and joined the team — another 10 percent share-holder in Quadra.

Working From the Heart

Quadra became a cult hit. “Much of our passion meant giving chairs to friends who needed them but couldn’t afford them, or selling chairs at a loss because we knew what a life-changing effect they had on people. Not the best business model, but for us it was more of a calling and passion than business,” recalls Boegel. A Quadra retailed for $500.

The team was commuting to Minnebraker’s house and building chairs one at a time in the cramped garage. “We were bending tubing, drilling, welding, assembling, often in the nude because it was so hot. Then we would jump in the pool, and get back to work,” recalls Boegel.

Soon Minnebraker sold his house and leased a warehouse in a small industrial park in Westlake Village.

The warehouse had a toilet and a tiny office in one corner. Parks took a small apartment near the beach; everybody else lived at the warehouse. At night they climbed up ropes to sleep on small lofts above their desks. Work-days started at 5:30 a.m. — one by one they would sit outside in the chilly pre-dawn darkness, naked on a plastic chair, screaming as icy cold water from a garden hose — their shower — hit.

It was a hands-on business, the guys building chairs while Boegel handled sales and marketing and truing wheels. Minnebraker continued research and development, continually refining the product.

On a mission to change the wheelchair world, they were riding a unique wave, experiencing the spiritual kinship and positive energy received when working from the heart. Breakfasts were at Phyllis Diller’s daughter’s cafe — often on a “tab” — Phyllis sometimes serving them. They ate cheap and filling dinners at a local Mexican restaurant.

On a mission to change the wheelchair world, they were riding a unique wave, experiencing the spiritual kinship and positive energy received when working from the heart. Breakfasts were at Phyllis Diller’s daughter’s cafe — often on a “tab” — Phyllis sometimes serving them. They ate cheap and filling dinners at a local Mexican restaurant.

“At night we would entertain ourselves by hanging in the factory, blasting Earth Wind and Fire music, dancing while we built chairs, sharing ideas, and overall having magic, passionate, creative fun. It was an amazing time,” says Boegel.

Parks says, “We put our whole heart and souls into the business, we didn’t hold back a thing.”

Indestructible

Since skeptics said aluminum chairs would never hold up, product testing of the frames and welds became an important focus. Boegel recalls testing frames by driving down the road at 60 mph and tossing them out of the back of a van. Even more impressive, Minnebraker would ride a wheelie and drop off of a 4-foot loading dock. The frames and welds held. Fortunately, so did Minnebraker’s spine.

Perhaps the ultimate product testing was done by wheelchair basketball’s Dave Kiley. “I was their test guy. If a Quadra could hold up to wheelchair basketball, it could hold up to anything. Jeff was a genius when it came to perfect alignment, camber and toe in/toe out,” says Kiley. “The frames were indestructible — they are probably still around today,” says Kiley.

At first Kiley’s compensation was equipment — Quadra chairs. “When things really got going, Quadra was paying me 20 grand a year to test and promote their chairs,” says Kiley. “Another wheelchair company offered me a huge sum of cash to leave Quadra and sign on with them. I wouldn’t do it because I was proud to be part of something that was changing the world. I was proud when I wheeled into the shop and saw rows of frames with all this color and anodizing, something that had never happened before.”

In 1978 the University of Illinois Gizz Kids outfitted their entire team with Quadras. Other teams soon followed. “Basketball team chair orders — 12 to 15 chairs — were huge,” says Boegel. “They also created a nationwide buzz that led to increased sales exposure and sales.”

They Caught On Quick

Most wheelchair dealers were still stuck in the “wheelchair user as a patient” model. An exception was Marty Ball, who was director of sales for Mobility Unlimited in Rhinebeck, N.Y., at the time. “I saw Jeff in a Quadra at a track meet in 1978,” says Ball, a wheelchair user and polio survivor. “As soon as I saw it, I got rid of my Stainless Super Sport, got a Quadra and became the first dealer out East to sell them.”

“They caught on quick,” says Ball. At first insurance wouldn’t pay for the chair because they didn’t understand it, even though at $500 retail, it was half the cost of contemporary folding wheelchairs. “Still somehow wheelchair users came up with the money,” he says. The first group that bought them were athletes and active people. “The big challenge was explaining that it was easier and quicker to transfer a rigid frame chair into and out of a car by folding the back and popping the wheels off with quick release axles.” Quick release axles for wheelchair wheels were one of Minnebraker’s innovations — something he adapted from the aircraft industry.

“I started getting invites to do in-services at rehab centers all over because people were going ga-ga over the chair,” says Ball. “When I showed them the light weight, and how a simple center of gravity adjustment would maximize the chair’s performance to meet their clients’ needs, therapists got it.”

The other dealer who enthusiastically embraced Quadra in those early days was Abbey Medical in Fresno, Calif., thanks to its director of sales and wheelchair basketball player, the late Wayne Kunishige. “Wayne was so full of enthusiasm for the Quadra chair and had so many ideas that I would set aside an hour of each work-day to speak with him on the phone,” says Boegel.

In 1979 Kunishige fit and sold a Quadra to Marilyn Hamilton, who had become a paraplegic in a hang gliding accident a year earlier. Hamilton would later team up with two other friends and start an extremely successful wheelchair company called Motion Designs to sell the first Quickies.

A Product Before its Time

Orders were flooding in for Quadras, but money was extremely tight. “Our goal was to improve people’s lives — to get these chairs to people around the country and the world,” says Boegel. That goal in mind, Minnebraker set up a business meeting with Everest & Jennings — the largest wheelchair manufacturer in the world with annual sales of $100 million — at its new offices and manufacturing plant in Camarillo, Calif.

“We hoped they would buy the idea and we’d stay on as consultants or go into partnership and have them manufacture the chairs,” says Boegel. “We were so enthusiastic.” They showed E&J the light weight and full adjustability, explained the chair’s higher performance and ease of propulsion, went over the aerospace technology integrated into the chair, showed how the quick release axles enabled ease of transfer into a car, and showed the different colored and anodized frames. Minnebraker finished the presentation by performing amazing spinning wheelies and chair moves, and then lifted a demo chair over his head with one hand.

“We figured they would be jumping up and down and cheering,” says Boegel. They had just handed E&J the future of the manual wheelchair business on a silver platter. But the E&J executives didn’t get it. “They literally laughed at us! Practically laughed us out of their offices,” says Boegel, who recalls E&J executives saying, “We are the biggest wheelchair company in the world. We know wheelchairs, you don’t. This type of chair will only work for, at best, 1 percent of the market. And it will be a dangerous liability for higher level injuries.”

Orders were flooding in, but without the deep pockets of a company like E&J, Quadra was running in the red. The team had great relationships with the vendors who supplied the materials to make the chairs, but their credit was tapped out. Broke and exhausted, relationships became strained.

The Revolution Lives

Because the business/medical world didn’t get it, and the chairs were primarily a cash item, the team entertained the idea of selling Quadras in bike shops — it seemed there was one on every corner.

Minnebraker sought a loan from an investor involved in the bike industry, someone he thought was a friend. Recognizing the financial toll, exhaustion and strained relationships, the investor used his checkbook as a tool to play them against each other and methodically gain control of the company. Parks and Boegel represented a threat because they opposed the investor’s plans. By 1980 they had been driven out of the company. “Eric was quieter. When things got stressful he would go to the beach and mellow out watching the waves. To the investor he didn’t represent a threat so he was allowed to stay on,” says Boegel. The investor wrested controlling interest from Minnebraker, brought in European investors and eventually drove Minnebraker out.

Kiley was driven out as well. “As soon as the investor gained control of the company, they stopped paying me,” says Kiley. “I had a family to feed. I had no choice but to sign with another company.”

For a while the investments worked and the company became profitable. Boegel recalls that sometime around 1986 the investor sold Quadra to Ortho Kinetics, but the company killed the whole project shortly thereafter.

The way the company ended took a devastating toll on all four team members. But they also feel a profound sense of pride, knowing they achieved their goal. They busted down the door and forever changed the paradigm of the wheelchair world. The amazing choices we take for granted today — custom-fit lightweight chairs, precision, high performance, color, style — all started with an idea and four young wheelers with the passion and perseverance to see it through.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair