Smoke was rolling out of the World Trade Center on Feb. 26, 1992 when WWOR-TV’s Chris O’Donoghue rolled up in his wheelchair — one of the first reporters on the scene. “I’ll never forget the blackened faces of the firefighters as they went back and forth evacuating people,” recalls O’Donoghue. “I never had time to panic for myself.” In truth, the water and fire hoses that icy day literally froze his wheelchair in place making it almost impossible to get out. He reported live for more than 12 hours and his work aired around the world on CNN.

Smoke was rolling out of the World Trade Center on Feb. 26, 1992 when WWOR-TV’s Chris O’Donoghue rolled up in his wheelchair — one of the first reporters on the scene. “I’ll never forget the blackened faces of the firefighters as they went back and forth evacuating people,” recalls O’Donoghue. “I never had time to panic for myself.” In truth, the water and fire hoses that icy day literally froze his wheelchair in place making it almost impossible to get out. He reported live for more than 12 hours and his work aired around the world on CNN.

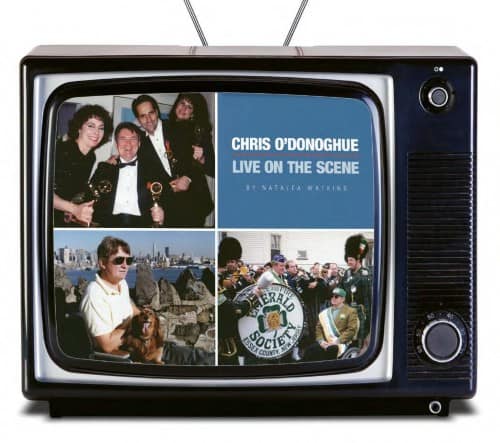

Crews from Japan, Germany and Turkey did stories on him, considering it real news that a guy in a wheelchair was covering such a big story on television. At 46 won his first Emmy for his reporting that day and later moderated a United Nations proclamation on the rights of persons with disabilities.

Over the next two decades he covered stories from the Central Park Jogger Rape to the Preppy Murder Case and won awards for reports on the plight of Irish Immigrants and the story of the Subway Bombing victim. He tweaked Mayor Rudy Guiliani for snowplowed piles that made Manhattan impassable for people in wheelchairs and to this day he boils that he can hail an accessible cab in London or Sydney but not in Manhattan. But he saw changes too. “After the ADA, people became a little more sensitive,” he says. “You’d go to interview a CEO and it was completely inaccessible but when you went back again they were proud to show you that they’d made changes.”

He says the station rarely assigned him to disability stories to avoid the appearance of exploiting him, but the reporters who were assigned often came to him for advice. He got lots of mail from viewers who had questions for themselves or for a disabled relative. In 1988 he was honored by the Ann Klein Endowment Fund for his work in the disability community and in 1993 he received the Henry Steiffel “Against all Odds Award” as a role model for people with disabilities.

But he also paid a price. Long days in freezing weather at the scene of breaking news and transfer after transfer into news vehicles or his own car led to two shoulder surgeries. The second took him out for over a year due to complications. “It was the first time I thought I might have to go back to Ireland so my family could take care of me,” says O’Donoghue. It was a real gut check for a guy who considers traveling alone in Australia and Thailand two of his most empowering adventures.

Attracting Attention

In 1965, 21-year old O’Donoghue arrived in Manhattan from Ireland determined to take a bite of the Big Apple as a professional soccer player. “I never expected to stay,” he says. “I just wanted to see the world.”

His sister Mary says the family was “utterly surprised” at his decision to head to America but “he’s always had a very independent streak.”

Two and a half weeks after leaving family and friends in Limerick, the popular athlete found himself alone in an American hospital. His legs weren’t working right. The diagnosis was a shock: arteriovenous malformation — an undiagnosed birth defect that would end his professional sports career and eventually limit his mobility. “It came out of nowhere,” says O’Donoghue. “No one else in my family has or had it and I’d never had a clue before.”

Certainly his family thought he should come home to Ireland and let them help. But O’Donoghue walked out of the hospital forewarned and admits he went as crazy as Manhattan was in the ’60s. “I had no perspective. I thought all of America was like this,” he says He played soccer, earned a college degree and lived like there was no tomorrow.

By 1976, the blood vessels in his spinal cord had ruptured — destroying nerves at the T10-L1 level — and he began using a wheelchair full time. Even the best of friends couldn’t haul him up and down the four floors to his apartment every day. He was forced out of his beloved Manhattan to a garden level flat in Brooklyn.

Rehab was a different animal in the mid-’70s. “Their idea of wheelchair sports was jumping curbs. There were no curb cuts. There was no ADA. Guys were coming in with gunshot wounds and injuries from car crashes. What camaraderie there was centered on suicide — not exactly an ideal atmosphere for rebuilding your life,” says O’Donoghue.

Nevertheless, rehab turned out to be his future. After a few of what he calls “angry years,” he earned a master’s in rehabilitation psychology at New York University, where student housing was accessible. He even did an internship under Dr. Howard Rusk, considered the father of rehabilitation medicine. “In another internship I worked with guys battling schizophrenia and it didn’t take long to see that I didn’t have it so bad,” says O’Donoghue. He went on to form a rehabilitation consulting firm and followed his own fitness advice by taking up wheelchair basketball and tennis and maintaining regular workouts. “You get to choose between helping people and needing help. You don’t have to just sit around. I’ve seen a lot of people more pathetic on two feet than in wheelchairs.”

O’Donoghue’s best therapist had four feet — a long-haired dachshund named Rinka who saved his life, he says. The dog found the sweet spot under the axle of his chair and the two became a sort of synchronized ballet — no matter where or how fast the chair moved, Rinka maintained her position — tail wagging. O’Donoghue says he was often stopped by people who told him “There’s a dog under your chair” — as if he was unaware. But she gave him a reason to get out, reconnect and care about something beyond his changed circumstances.

Attracting attention was a skill learned early by an Irishman born in the middle of four brothers and two sisters in a close Roman Catholic family. O’Donoghue made frequent trips back to Limerick to see them and a growing number of nieces and nephews. In 1983, the whole family turned out to see him off and the crowd, plus the novelty of the aisle chair, caught the attention of a fellow traveler who turned out to be an American television executive.

Luck of the Irish

You’ve heard of the luck of the Irish, but O’Donoghue’s next chapter is still almost unbelievable. It turns out that his fellow traveler, Lawrence Fraiberg, was the president of Group W Television and the group’s Baltimore station had just signed a contract to broadcast the Baltimore Blast professional soccer team. Fraiberg challenged O’Donoghue to submit an audition tape to become a sportscaster.

“I thought the whole idea was hilarious,” he says. “But what did I have to lose? I knew I didn’t want to just sit behind a desk somewhere.” O’Donoghue says a friend in the public relations business had a video camera and they used it to shoot a sportscast. Writing the script was a bit of a challenge since he’d never learned to type, but no more ludicrous than the rest of the situation. He got the job and found himself a bit like the dog that’s caught the car he was chasing. Now what?

“They didn’t quite know what to do with me. At first, they didn’t want to show my wheelchair on the air so they had me sit on crates and other things until people got to know my voice with the Irish accent and all.” Eventually, he was shown in the chair and there was no public outcry so it ceased to be an issue. He enjoyed traveling to away games and at least he was in Baltimore where none of his friends could see him learn on the job.

The real issue for O’Donoghue was the time the Blast wasn’t playing. He was assigned as an associate sports producer covering football, baseball and other American sports. “I didn’t grow up with those sports, didn’t know the rules and didn’t particularly like watching them,” he admits. “It seemed like all I did was ask the same questions of another opposing team every week.” The good thing about the sports gig was that it generally happened on a schedule and in a pre-arranged location, which made things a little easier for a guy trying to figure out how to get there in a wheelchair.

Finally O’Donoghue suggested he be reassigned to general news. Suddenly the “carefulness” started all over again. He was only assigned school-related stories where the venues were considered “safe” until the afternoon a big fire broke out while all the other reporters were still in editing. He was sent as a “microphone stand” until a “real” reporter could arrive. But by that time, he’d already gathered the information from firemen and policemen who recognized him and helped him over the hoses. “I wasn’t about to let someone else do that live report on the 6 o’clock News,” he says.

So began his life as a TV newsman where he likened riding in a LIVE van in a wheelchair to being a loose fork in a silverware drawer. Much of the time he followed the van in his own car. “Some crews bent over backwards to help and some did as little as possible,” he says.

Wayne Butrow is a videographer in Baltimore who remembers those days. “I did my thing and he did his,” says Butrow about O’Donoghue. “He was pretty independent and certainly never asked me to push his chair. Mostly he was trying to learn how to be a reporter and working really hard at it.”

Two years ago, he retired from WWOR. It’s been a challenging transition. O’Donoghue loves having his privacy back, traveling and being a “culture vulture” in New York. But he’s also facing the challenge of reinventing himself again. “I realize I disappeared from the Rolodexes of a lot of people I stood up for dinners and theatre dates when a news story stretched into a live shot on the late news,” he says, noting it’s a little late to explain that he really didn’t have time to call.

O’Donoghue considers a “bucket list” a uniquely American conceit, but admits to trying jet skiing for the first time last month and loving it. His 70th birthday is approaching with shocking speed and yet he’s pretty sure there’s another great passion out there awaiting discovery. “Who could have imagined the life I’ve had so far?”

Life is Funny

In the early ‘80s, I was a TV news director in Baltimore with a sports reporter named Chris O’Donoghue who used a wheelchair. Nearly two decades later, a car accident put me in a chair as well. My memory of Chris’s ability to handle everything life threw his way made me fairly unconcerned when doctors told me I wouldn’t walk again. They thought I was in denial. I thought I was lucky to have had a good role model. I even tried unsuccessfully to contact Chris.

Then, last year, I noticed a letter to the editor in NEW MOBILITY from a Chris O’Donoghue in Ireland. It seemed such a coincidence that I asked NM’s editor, Tim Gilmer, if he could get the guy’s e-mail address. Turns out it was the Chris I knew, and we exchanged a few e-mails comparing retirements and the coincidence that we were both in chairs now.

It wasn’t until Tim suggested I write a story about Chris that I learned more details: He’d been an athlete in his 20s and I was a nearly 50-year-old woman with a desk job. Also, his level was T11-L1 and mine was T5. I was embarrassed to tell him I had wimped out to a power chair and a ramp van about eight years ago. He said he uses a power chair most days now as well. Maybe I had held myself to too high a Chris O’Donoghue standard through the years.

I got a chance to apologize for having him carried to staff meetings held in a second floor conference room in the days before the ADA and worrying about how to “safely” send him out to cover breaking news. What do they say about hindsight being 20/20? … especially in this case

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair