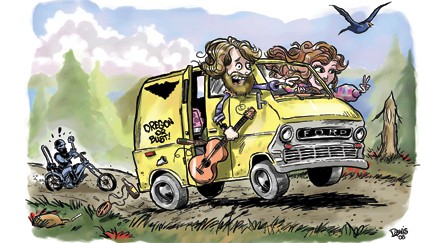

When Sam and I headed north on I-5 from Bakersfield in her mustard yellow 1971 Ford Econoline van with the unfinished, hand-painted Harley wings on the sides, we knew it would be no ordinary road trip. Back in my pre-wheeler college days, I had escaped smog-choked Los Angeles numerous times in the wee morning hours, hell-bent for who-knew-where after consuming prodigious amounts of beer. And Sam had fled the work-grind on many a weekend to camp in the woods with her semi-biker husband, Wes. But now we both needed to escape disappointing past lives and make a new beginning — whether as friends or more-than-friends, neither of us could say.

It was 1974, the ‘60s still glowed — a bed of dying embers — and thanks to the OPEC oil embargo, gas prices had skyrocketed from .38 to .55 per gallon. Sam’s van — Bodacious — was good for a modest 14 miles per gallon, so we agreed to keep him on a short leash, when what we really wanted was to fast-forward to an uncomplicated future somewhere in the Northwest woods.

Her marriage had imploded a scarce four months earlier. During that time I had done my best to draw the line at being a friend to her, to ease her discontent. I’d even tried to contact Wes — to ascertain his intentions toward her — but he was too busy with his Latina mistress to respond. It was then that my friendly focus began to morph into a nameless emotion, and I decided to chance escorting Sam to her new life. Our only plan was to travel to Oregon together, to see what it had to offer. After that, we could go our separate ways, or … but beyond this point I would not allow myself to envision possibilities.

Bodacious rolled alongside the white line rakishly, his stylish snubnose tilted forward, baby moons reflecting the morning light, the midday glare, the sun descending in the west. His Harley wings were pure unadorned black, no detail. Shadowy symbols celebrating the freedom of the open road. Besides being handsome enough to turn heads, Bodacious was comfy, well appointed. Southwest Native American-motif curtains separated the cab from the bed, which really was a bed — four inches of foam covered with indoor-outdoor carpet. The paneled walls had only one obvious defect, a nasty gash where Wes had punched a hole in a temper tirade. I had never seen this Wes in action, only the sedated one, stoned on weed, hash oil or, as legend had it, peyote. But it was well known that Wes could be violent.

Sam had told the story more than once of how Wes jumped down from behind Bodacious’ steering wheel at a stop light, ran up to the car in front of them and kicked great dents in the door while the terrified driver cowered in disbelief. “No one cuts off Bodacious, asshole!” he screamed, pounding on the driver’s window.

She laughed when she told that story, but she knew Wes’ temper intimately. I had heard about the black eyes. Still, she was no battered woman — she had fought back. But at 5 feet 3 inches and 105 pounds, she was no match for Wes. All that was fading now, left behind as Bodacious cut through the interminable boredom of the largest agricultural valley in the world: dry dusty Bakersfield, deep-fried Fresno, sizzling Sacramento, Red-hot Redding, heading for the tiny town of Yreka in the Siskiyous before descending into Oregon.

Sam did the driving, her long auburn hair streaked with gold from the sun. At 25, she was leaving behind a childless marriage of seven years with Wes and a failed motorcycle chrome polishing business that attracted a lot of Hell’s Angels types. The unfinished Harley wings were all that was left of that dream.

The late afternoon sun illumined a fine fuzz that outlined her forehead, nose, and jaw. I loved that view. From the passenger seat, I wondered what it would be like sitting in the driver’s seat behind shiny new hand controls. But no … that was assuming too much.

At 29, nine years post-SCI, this trip was a huge move for me. Since becoming paralyzed, my prospects for happiness and success had steadily plummeted — lost jobs, lost love, lost direction, two return trips to the hospital for surgery on infected pressure sores. Now, finally recovering from heartbreak and depression, I carried with me only a few mementos of my past: a box of high school sports medals, several get-well cards I kept following my plane crash, the two 9-inch Harrington rods I had insisted a hesitant surgeon remove from my back. And, oh yes, my classical guitar. Everyone who survived the ‘60s traveled with a guitar. When the mood struck, I climbed down from the passenger seat and crawled to Bodacious’ cushioned bed to work on a medley of almost-songs I’d been working on for too long.

Sam’s wounds were much fresher than mine, but her spirit was reviving, thanks to a strong constitution, her still-intact dream of escaping East L.A., and my constant concern, I liked to think. She had brought along a few of the things she loved — incense, bells and chimes, a pair of slip-on pumps made from Levi fabric. She was fond of wearing Levi’s, tie-dye shirts that buttoned at the neck and a bone armband that showed off her shapely arms.

Neither of us had crossed the California/Oregon state line before. When we began the descent into the Rogue Valley, we were greeted by the infamous “Don’t Californicate Oregon!” sign. Although intended as a plea for Golden State escapees to leave Oregon in its unspoiled condition, it seemed almost like a providential warning. Sam and Wes had made a clean break, but they were still legally married. I would have to be careful.

Gliding into magical, green Ashland just over the Oregon border, we relished the purity of anything un-California-like: cars that obeyed speed limits, roads with room to roam, greenspace everywhere bordered by tall trees, and water enough to sprinkle a lifetime of dreams. We took up residence for two weeks in the driveway of friends of mine from college, mooching bathroom privileges and peppering them with questions about Oregon. Cooper and Kat were among the first Cal-migrants from the ‘60s to land in God’s country.

Crossing the state line was like disconnecting from the past. Each night we slept side by side in Bodacious on our plot of concrete, inventing novel ways of ignoring the obvious: The longer we were together, the more likely we were to break all the rules. Yet somehow we felt innocent.

Every day we took off in Bodacious in the morning and explored, not knowing what lay around each corner, then returned to our concrete pad at night. We drove east toward Klamath Falls as far as Howard Prairie Lake, west through Jacksonville into the smaller Applegate Valley, north toward Crater Lake, following the Rogue River, climbing until the fir trees thickened and the cool spring air turned cold. Always we returned before sundown, shared our day with Cooper and Kat, then retired to the privacy of Bodacious each night, where soft guitar chords and incense lulled us to sleep.

After a week of driving and exploring, one day we decided to pick up a local paper and check the classifieds. We were curious about the cost of rentals. Our curiosity lured us to inspect a rental house in Medford, and another in Jacksonville. And just because it seemed like fun, one day we visited an isolated newer duplex in the country with a large screened-in porch and a quiet view. The rent was surprisingly low.

We never talked of getting a place together, yet it seemed like some unseen force was urging us in that direction. During the second week of the road trip, each evening when we returned in Bodacious to Ashland and parked in Cooper and Kat’s driveway, we went to sleep in each other’s arms. The next morning we would wake up staring into each other’s eyes. We never spoke of the future. It seemed we could go on forever being content with the present.

Finally, one night in the back of Bodacious, I said, “You know, I really like that place in the country. It’s so peaceful and isolated, yet not too far from Medford.”

“Yeah, I like it, too,” she said.

“We haven’t really talked about this, but, you think …?”

“Yes, I do,” she said. “I think I’d like to live there.”

The next day we rented the duplex in the country and headed back to Bakersfield in Bodacious to gather all our belongings. A week later we re-traced our I-5 trip, Sam in Bodacious and me in my ‘69 Chevy Malibu. When we arrived at the isolated duplex where we had planned to make a new beginning, we were utterly alone. We didn’t even have a phone. We liked it that way.

Once settled, we went job hunting. I got a job selling electric organs, thanks to Voc Rehab subsidizing my first six months on the job, and Sam pumped gas at an all-girls discount gas station. Each night we sat inside our screened porch and watched the sunset. We adopted a puppy from the pound. We planted a garden. An older lady who almost bought an electric organ gave me a set of used hand controls that had belonged to her recently deceased husband. “They meant too much to him to sell,” she said.

On weekends we took off in Bodacious and explored. Most of the time I drove, relishing the feeling of being in control of the road, if not our destiny. I bought an inflatable raft, tossed it in the back of Bodacious and we went camping. We drove backwoods roads and swam in mountain lakes. We were happy together. The road trip had not ended. It was just beginning.

It was toward the end of summer when the poetry started arriving each day in the mail. At first I hardly noticed. Then one evening I saw that Sam had been crying. “What is it?” I asked. “Is it Wes?”

She nodded. “He wants me to come back.”

Now he wants her, I thought. Six months without speaking a word to her or showing any interest whatsoever and then one day he decides he wants her.

The poetry was bad, very bad, but it spoke of seven years of marriage. Sam became more and more depressed. Each day a letter from Wes arrived, and each day she went to the screen porch by herself, or outside in the garden, or for a walk, reading bad love poetry from the same man who had blacked both her eyes, and each day her face lost some of its glow. The light in her eyes seemed duller. Even her shiny auburn hair seemed lifeless. It was then that Sam told me Wes had boasted of having a plan to take me out when talking to her brother, mentioning biker types, killing, marks, contracts. At the time she thought it was just tough talk. As for me, now was no time for doubting his word.

The earliest he could arrive would be about 5 or 6 p.m. the next day. I envisioned hiding behind the front door with my 34-ounce Jackie Robinson thick-handled baseball bat in my hands. When Wes walked in, I would coldcock him. I’d have just one swing. It would have to be a solid slam to the head, quick and sure, followed by a vice-like stranglehold. If Wes was still on his feet after I connected with the bat, my wheelchair would most likely topple over in the struggle and we’d wind up on the floor. I’d have to hang on to Wes’ neck with everything I had and choke him until he went blue in the face.

But what if Wes was holding a gun when he entered? I’d have to knock it out of his hand with the bat. Once again, I’d have just one swing. How strange, how odd that the one thing I had done better than anything else in my pre-paralyzed life, swing a baseball bat, the thing I thought I’d never do again, had now become the skill, the tool — the weapon — that my life now depended on.

Why not get a gun? I could buy one first thing in the morning. No, I couldn’t see myself shooting Wes. They’d say it was premeditated, murder for God’s sake! Not self-defense. And how could I do it? I didn’t even dislike Wes. I had smoked weed and hash oil with him in the days before he and Sam split up. I shot pool with him, told jokes and laughed with him, listened to his stories. But how can you like someone who has sworn to kill you?

Sam turned toward me and sighed, head on her pillow, eyes still closed, her face tangled in her long hair. That beautiful hair, entangling all of us now.

The next morning I woke with a sensible plan. “I know what to do. When Wes comes, he’ll find nothing. We’ll take Bodacious and go camping somewhere. He’ll come to an empty place, if he can even find it. Without Bodacious here, he’ll never find us. I’ll park my Malibu in Medford. We’ll stay gone for a day or two.”

Sam was OK with the plan. She was run down, mentally and emotionally exhausted. She needed rest, and to be left alone. She needed a break from bad love poetry. I needed a break from death threats.

I drove Bodacious to a 5-acre plot of land in the Applegate Valley owned by Cooper and Kat, far from I-5. There we camped for two nights, trying to forget the circumstances, courting the illusion that our road trip had just begun. But now the future seemed distant and dark. We had both missed work. It was Monday night when we returned to the duplex.

We drove up the long dirt driveway slowly, me in my Malibu first, carefully surveying the situation, Sam following in Bodacious. Wes was not there. We entered the house and looked around. Nothing disturbed. We had not slept well in Bodacious the previous two nights. We went to the bedroom and instantly fell asleep in my waterbed.

The knock at the door startled both of us awake. It was morning. Before I could pull on my pants and get in my chair, Sam had gone to the door in her nightie and returned with a piece of paper in hand. “A county sheriff,” she said. “Wes had an accident. He was on his way here on his motorcycle and crashed. His leg is messed up and he wants me to come get him in Bodacious. He’s at a motel in Redding. He wants me to call him at this number.”

“What are you going to do?”

“All I know is I’m with you now, and I’m not going back, but I need to call him.”

I drove her to a phone booth in Medford and waited in the Malibu. When she made the call, she broke down, sobbing. It was the first time she had heard Wes’ voice in over six months, and she was softening. My instinct for self-preservation kicked in. I quickly transferred into my chair and rolled to the phone booth just in time to hear her say, “Okay, I’ll be there as soon as I can,” then hang up. My right hand flew from my side and slapped her face, stunning her. I didn’t mean to hurt her, had never considered such a possibility, but the sudden passion — the possessiveness — had subdued my better nature instantly, as if it had a life of its own. It was the first and only time I ever struck a woman.

We rode back to the duplex in silence in the Malibu. The road trip was nearing its end. I felt as if I had been betrayed, but when I glanced at Sam, her red-rimmed eyes welling with tears, I suddenly felt ashamed. At my selfish core, I was no better than Wes. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I had no right to do that. This is your life, your marriage.

I knew I was taking a chance from the beginning. You should do what your heart tells you. I’m sorry. I never want to hurt you. Go to Wes. Take Bodacious and go to Wes.”

Sam called a friend with a van, who picked up Wes and his motorcycle in Redding and took him back to Los Angeles. A few days later, she drove off in Bodacious, heading to California. She got as far as her mother’s house in Bakersfield, then called Wes. But after talking with him on the phone and confiding in her mother, she decided against going to see him. Back she came, crossing into Oregon in Bodacious for the third time in the last several months.

We were running out of money. I was a lousy salesman and Voc Rehab stopped subsidizing my pay at the piano/organ store, so they fired me. Sam found a cheap house in Medford that rented for $125 a month. The interior walls were like cardboard, it was tiny, and black widows lurked in the corners of the old garage. But it had a garden space.

We bought a kitchen table at a garage sale for $7, a decent sofa for $90, and a used refrigerator for $40. I sprayed the black widows and gathered the old lumber someone had left in the garage and knocked together a long, low sturdy bench for my stereo system. Sam set the asparagus fern her mother had given her on an old stump near a window. That night I dreamed that an army of black widows was advancing toward the house. In the morning I went to the garage and sprayed again.

We had furnished the house for only $137 but weren’t making enough on Sam’s gas-pumping check to make it. I applied for food stamps and was approved. We got $80 every month in food stamps.

Something was missing. On our weekend trips I no longer felt at home behind the wheel of Bodacious. The shadow of Wes hovered over us. The unfinished Harley wings were a constant reminder of the unfinished life that Sam had left behind. We couldn’t go on, dragging the past along with us. My heart was in conflict. Finally, I told Sam she needed to make one last trip to Los Angeles. She owed it to herself, to Wes, and to me. All three of us needed a solid resolution. I decided to remove the hand controls from Bodacious — then changed my mind.

Sam left in Bodacious for yet another trip south. Jobless, I lay on the waterbed and tried to imagine a future without her. This time I knew she would not come back. When she came face to face with Wes, she would not be able to control her emotions, and if that happened, I’d have to be OK with it. Maybe I could go back to college and get a graduate degree. In the meantime, I had food stamps, Social Security and my stereo.

After Sam reached Los Angeles, she called. Before answering, I took a deep breath. “It’s me,” she said. “Well, I’m here, and I’ve seen Wes. I’m in a phone booth not far from his place. He wants me to stay. He’s been crying and begging me to come back.”

“What do you want?”

“I’m not sure. He seems different. I thought I’d be angry, but I feel sorry for him. Part of me wants to stay and make things right, and part of me doesn’t.”

“I understand. Seven years of marriage is a long time together. Listen, you know I love you, but nothing will be right for any of us until you make up your mind. This is about you. You have to make the choice for all of us. You have to do what your heart tells you. Don’t be swayed by him and don’t be swayed by me. Do what is best for you. Whatever you decide, it will be right.” There it was, I had said everything I had to say, and I meant it.

“I understand. Seven years of marriage is a long time together. Listen, you know I love you, but nothing will be right for any of us until you make up your mind. This is about you. You have to make the choice for all of us. You have to do what your heart tells you. Don’t be swayed by him and don’t be swayed by me. Do what is best for you. Whatever you decide, it will be right.” There it was, I had said everything I had to say, and I meant it.

“OK.”

Two days later Bodacious pulled up in front of the house with the cardboard walls. Sam was driving. I opened the door and rolled onto the concrete porch, not knowing if she was coming back to get her things or to begin the new life together that we had dreamed of at the beginning of the road trip.

She was wearing her bright red tie-dye shirt that buttoned at the neck, her bone armband, Levi jeans, and her Levi material pumps. Her long hair was newly washed. It was late afternoon and she looked prettier than I had ever seen her as she stepped onto the wooden ramp that Cooper and I had built. When she reached the top of the ramp, she dropped her purse and her keys on the concrete, smiled broadly, eyes sparkling, and hugged me. I hugged her back, my heart lifting. We kissed, and then we kissed again. “I promise you I’ll never leave you,” she said.

The road trip was over. The promise — 34 years and counting — still stands.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair